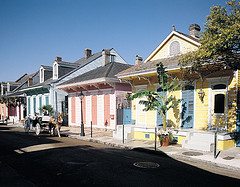

French Quarter Post-Katrina Photos

By: FrenchQuarter.com Staff

The New Orleans French Quarter after Hurricane Katrina looks pretty much the way it did before. Thank goodness. And residents and shopowners have been busy cleaning, polishing and sprucing up the old city for company coming. FrenchQuarter.com’s been on the streets taking pictures of Second Lines, psychics, artists, street sweepers and assorted characters who give the French Quarter its unsinkable mojo!

If you’re visiting the French Quarter, check out all of your options – here’s the list of open restaurants, hotels and shops plus their Katrina hours of operation.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Inspired by Decline: Old Quarter Feeds Creativity

If “the seed must die to generate new life,” it was the post Civil War demise of the old Creole society in the New Orleans French Quarter that gave rise to a world of romantic reminiscences about it. Those enigmatic Creoles– be they private, penurious, prideful in their poverty–left their indelible mark on the world they built. The sprit of what went before absorbed and co-opted those who came afterwards, those who inherited the remnants of the kingdom. Living with the dense, semi-fortified streetscape, a world of light and shadow known for withholding some of her favors, they came to grips with the sense that something about the place and the people was elusive. Thus was born the New Orleans fiction of George Washington Cable and Lafcadio Hearn, of Grace King and Kate Chopin, in the waning years of the 19th century. As historian S. Fred Starr has written of Hearn especially, they “invented New Orleans.” And if Creoles resented being probed and analyzed, ridiculed and fictionalized, perhaps it was because they were the un-self-conscious, uninvented, genuine article.

Time wore on and time wore down the neighborhood. No longer a place of grace and wealth, it became a place for the displaced, for the poor, the immigrant who lent his flavors to the heady mix of place and people. It all came together at the Old French Market, where the scenes and scents of vital life swirled into a piece with historic precedent. This was a place for those who were comfortable with a dense urbanism, risk-takers who found a little or a lot of dirt and disorder, clutter and confusion somewhat acceptable.

Nineteen hundred was the winter of existence in the life of the Quarter. Its people were as poor and as worn as its streets and its buildings. As the one-eyed, night-watching Hearn had recounted, the populace lived in warrens, washed food and body in courtyard fountains, and worked from dawn to sunset. But if the seeds of growth were buried, the earth was fertile. Photographers arriving in 1920 were as astounded to see it as archaeologists finding treasure. With careful lens they captured the Quarter as it emerged unretouched from its postwar decline. Scenes captured by photographers Tebbs and Knell of the 1920s presented a stark contrast to the polished views commissioned by the city in the work of Lilienthal fifty years earlier.

Writers and painters followed. The starving artist could find in the Quarter an inexpensive room with a picturesque view of rooftops looking like Left Bank Paris, piano music drifting upward, and kindred spirits, human and bottled, at every neighborhood corner. If it is a natural part of an artist to find virtue in decay and a sultry atmosphere, saints abounded. William Faulkner, writing from a Pirate’s Alley flat in 1925, composed this take on Jackson Square at nightfall:

“He opened the street door. Twilight ran in like a quiet, violet dog, and nursing his bottle, he peered out across an undimensional feathered square across stenciled palms and Andrew Jackson’s childish effigy….” – (Mosquitos, 1927).

Writers of the Twenties and Thirties flocked to the Quarter. Along with Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson, Ernest Hemingway, Thornton Wilder, Roark Bradford, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Lillian Hellman, Lyle Saxon, and Hamilton Basso were among those who found their way to the Old Square of New Orleans for inspiration. They found it in peeling paint and shadowy, overgrown courtyards, in a heavily Black and ethnic population, in an environment where people lived out customs, found parts of day-to-day survival on the stoops of crumbing cottages, and valued old things, because in them, one found comfort.

Peeling paint and timeworn surfaces have given way to fun, food and entertainment. But the Quarter’s atmosphere of creativity has endured for residents and visitors. Try your luck with inspiration in a quiet corner. You just might be surprised to find it.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who co-authored the award winning series New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf – An Early History. She is currently working on a social and architectural history of New Orleans public markets and on a book on the contributions of free persons of color to vernacular architecture in antebellum New Orleans.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

French Quarter Fire and Flood

Top to bottom: Notable French Quarter Fire Survivors – Ursulines Convent, Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, Madame Johns Legacy

Of all the forces that conspire to destroy a city – time, storm, neglect, need – fire does the most harm. Without Prometheus, we might have more of our colonial city to preserve and savor. Two great fires in late eighteenth century New Orleans left the inhabitants few years to re-establish their institutions before the onset of American domination in 1803. Although several fine houses date to the last colonial decade, they and the French Quarter, including the Cabildo and the Presbytere, are conspicuously “Post-Fire.”

Looking at the vibrant, festive Quarter with millions of visitors annually, it is hard to imagine the devastation of Holy Saturday morning in 1788. Smoking ruins stretched from Chartres to Dauphine Street, and from Conti to St. Philip. The fire began on Good Friday morning in the home of Spanish treasurer Don Vincente Nunez at Toulouse and Chartres. It was a blustery March day, with the wind blowing out of the southeast (probably into a cool front). Within hours, over eight hundred homes and public buildings were reduced to ashes, including the church, the town hall, and the rectory on the Plaza de Armas. A saddened Governor Esteban Miro reported to Spanish authorities of the “abject misery, crying and sobbing” of the people. The faces of the families, he wrote, “told the ruin of a city which in less than five hours has been transformed into an arid and horrible wilderness; the work of seventy years since its foundation.”

The Second Great Fire

Rebuilding had scarcely begun when in 1794 a second fire and two hurricanes swept the city. The fire of December 8 that year burned 212 buildings – fewer, but more valuable. When both storms and both fires were all done, nearly all the public buildings, homes and businesses except those fronting the river had been consumed or badly damaged. Through it all the Ursuline nuns in their convent on Chartres Street had prayed to Notre Dame de Bon Secours, Our Lady of Prompt Succor, patron of Rouen, their home town. As the fire had neared the convent on that Good Friday, the wind changed suddenly. (As Providence would no doubt have it, the front arrived from the north just in time.) The convent survived, and is still here with us.

The results were fundamental to the Quarter. Baked tile and quarried slate replaced the roofs of ax-hewn cypress shingles. Buildings, set at the sidewalk or banquette, were of all brick, with common firewalls. The wide and shallow hipped roof, galleried townhouse perfected in the French period gave way to vertical, long and narrow Spanish-style town homes, many with overhangs, iron work and entresols or mezzanines. The Cabildo and Presbytere came into being. A new church rose from the ashes. A suburb opened on the upper side of town for residents wary of crowded Quarter conditions. Fire pumps were commissioned. The market moved riverside. Artisans were called in. Protestants gained a foothold. But people went homeless, the city indebted, and lives were lost to death or removal. The city was different.

Every Quarter Square Scarred by the Elements

Since the two Great Fires, Providence has not seen fit to visit the Quarter with any more all-points conflagrations up to the moment. But hardly a square in the Quarter has not had its smaller fires. And hurricanes keep coming. A great storm of August 19, 1812 swept away a brand new, year-old French Market building. Another in 1915 damaged the steeple of St. Louis Cathedral. The popular Orleans Theater and Orleans Ballroom burned in September 1816; rebuilt, the theater burned again in 1866. Fire damaged the Bank of Louisiana on Royal Street, today the home of the Vieux Carré Commission, resulting in the monumental columns installed in the remodeling.

Today, the French Quarter fire code is stringent. Motorized Mardi Gras parades are forbidden. Any Quarter fire signals an instant citywide fire alarm. The intent is to prevent fires from spreading. Still, the most important fires of the Twentieth Century occurred at individual structures. Social historians consider the burning of the Old French Opera House on Bourbon in 1919 the “final nail” in the coffin of the old Creole culture in the Quarter. But others espoused that culture, treasuring its memory. When the Cabildo burned in 1988, two hundred years after the First Great Fire, citizens felt the loss keenly. Carefully restored, it stands a proud reminder of a city’s resolve to safeguard its heritage.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who co-authored the award winning series New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf – An Early History. She is currently working on a social and architectural history of New Orleans public markets and on a book on the contributions of free persons of color to vernacular architecture in antebellum New Orleans.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Some Liked It Hot: Open-Hearth Cooking In Emerante Hermann’s 1830s Kitchen

Come see the open-hearth cooking demonstrations at the Hermann-Grima House

Nineteenth century foodways are on the menu Thursdays in season at the open-hearth kitchen of the historic Hermann-Grima House on St. Louis Street. Where Samuel and Emerante Hermann’s enslaved cooks Charlotte and Sarah once dished up Creole cooking in the 1830s and ’40s, trained volunteers now fire the coals under swinging cranes suspending smoked hams and spiced sausage. Carefully, they recreate the cooking procedures of the open hearth, the “beehive” baking oven, and the “potager” or “stew holes,” a brick-surfaced cavity capable of simmering gumbos, stews, and red beans. On the large rotisserie of the open hearth, volunteers roast ducks, chickens, geese and beef, or place meats in a “tin kitchen,” an up-to-date gadget of the 1830s. The curved tin contraption made roasting easier for early cooks by reflecting heat from the fire and catching juices. One could also comfortably baste meats through a door in the rear. Right in the fireplace, one could also cook “down hearth” on a short-legged grill, or bake soda-leavened cornbread in a lard-greased Dutch oven.

The cooks bake bread loaves—whether French, round or brioche—in the great walled oven. An experienced cook can use the arm to test when the oven heat is ready, counting seconds at the rate of “one potato, two potato.” At a tolerance of “ten potatoes,” the oven is ready for the loaves to be baked right on the floor inside (presuming the arm has been extracted). The simple dough of flour, yeast and water, with a small pinch of salt or sugar and a dash of milk, is inserted on a paddle. The cook may also swab out the oven with a water-dipped cloth, depositing the moisture needed to crust up the French bread.

What’s good at the Market? Beef for sale, 3¢ a pound

Servants of Creole families shopped for meats, vegetables, and fruit each morning at the old French Market. Until early in the twentieth century, the highly regulated public market was the only location in the Quarter where butchers and vendors could legally sell meats and other perishables. Sunday morning market days were busiest and most appealing for socializing, as shoppers purchased items for the sumptuous noon meal. More than beef, veal, lamb or pork, mutton was a highly prized item. Early in the 19th century, beef was poor, but cheap, at 2-3¢ a pound. One could purchase a pair of hens, chickens, capons, geese or ducks for 60¢ to $1.40. Two large turkeys cost $4.00, and eggs were about 20¢ a dozen. Market hunters supplied deer, snipe, partridge, mallard, teal, quail, rabbits, hare and the tasty red squirrel that feasted on live oak acorns.

“First class” fish from Lake Pontchartrain—including trout, eel, redfish, and perch, cost 6 to 9¢ a pound. Fishermen sold the more common river fish, probably cats and Tchoupic or mudfish, directly from their boats at a cheaper price. Other seafood in the market included oysters at 50¢ per hundred, crawfish at 11¢ for 20, and shrimp at 11¢ for 30. As early as 1800, the shopper could choose kale, green beans, tomatoes, leeks, Havana bananas, apples, peaches, plums, figs, and pomegranates at 11¢ to 20¢ a bunch.

A great pastime of shopping was drinking chicory café au lait at marble-countered market stalls. Chicory is the roasted and ground root of chicoroium endiva, which probably came into use in New Orleans about 1820, soon after the French began to grow it in Paris market gardens. Englishman Charles Lyell’s writings about the French Market in 1856 still ring true: “There were stalls where hot coffee was selling in white china cups,” he wrote, “reminding us of Paris.” New Orleans people still drip their coffee slowly in French biggins, and flavor it with chicory. Don’t go home without it.

Open Hearth Cooking Demonstrations are part of the guided tours offered Thursdays at the Hermann-Grima House, 820 St. Louis Street. 504-525-5661.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who co-authored the award winning series New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf – An Early History. She is currently working on a social and architectural history of New Orleans public markets and on a book on the contributions of free persons of color to vernacular architecture in antebellum New Orleans.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Is the French Quarter French? Or Spanish?

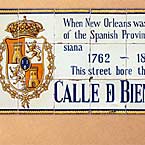

Spanish Influences: Memorial Signage of Original Spanish Street Names, Arched Entresol Building Design, Mezzanine & Courtyard View, and a Covered Courtyard Entryway

The age-old battle between the French and Spanish influence on New Orleans lives on. An intellectually savory argument, like angels dancing, it has fewer participants than in earlier decades when legal scholars contested the French-or-Spanish sources of the Louisiana Civil Code like knights in armor. Today the rivalry between the colonial powers lies mainly in analyzing French Quarter buildings and lifestyles. People ask: is the French Quarter French or Spanish? The arches and courtyards, the funny-looking “in-between floors,” the iron lace galleries, the café life and cooking ways-whose gifts were they? It is a subject for a café au lait at the market or a Sazerac at Napoleon House. After a few of those, the discussion can get heated, particularly when one’s know-it-all brother-in-law claims all the answers.

We confess that the French could have done a better job in the 18th century when the colony was theirs to win or lose. They chose to lose it, but the people chose not to be abandoned. Settlers clung to their French-born language and customs like moss on oak trees. From Paris they ordered all the latest editions of the golden age of Louis XIV and the French Enlightenment, filling their libraries with little 7-inch duodecimo sets of Racine, Moliëre, Voltaire and Rousseau. After forty years of Spanish dominion, they were still cooking with butter, marrying their cousins, avoiding their Easter duties, raising cattle with curious names like Fronzine and Bélizaire, and upholstering furniture with blue and white stripes in the Béarnaise fashion. They still had civil law, Mardi Gras, coffee dripping, the family meeting, sour oranges, sugar cane, Sunday dancing, and heavy gambling. They started drinking chicory coffee soon after French market gardeners began supplying the root of chicorium endiva to Parisian markets. Butchers at the public market-built by the Spanish-were so exclusively French that people began to refer to the French Market, in the “French” part of town, an institution left by the Spanish but built by Creoles and designed by a French native. The Quarter’s par terre gardens continued in the French style with flowers in the middle and walkways on the boundaries. The modern taste for a grassy lawn was either unheard of or an American malady.

French Influences: City Planning, Creole Cottages, Parterre Gardens, and a City Square ‘Overlooked by Church and State”

But forty years of Spanish dominion left the French Quarter with a semi-fortified streetscape ready for fighting the forces of evil, with phalanxes of common-wall buildings, mysterious alleys, and secluded patios. If the Spaniard’s flat-topped tile-roofed buildings worked better in Sunny Spain than in wet New Orleans, there are still a few out there on kitchens and privies to puzzle the visitor. The Spanish gave us the St. Louis cemeteries, St. Charles Avenue, the first Catholic bishop, olive oil cooking, jars in the courtyard, entresol buildings with mezzanine spaces, Pere Antoine-who was really Friar Antonio, and Baroque-looking government buildings. They also left that queer legal pleading, the non numerata pecunia, sent from the wise Alfonso in the thirteenth century. This rule specified that if the notary did not see money change hands during the course of a mortgage contract, the lender had to renounce his right to sue about it later. The burden of proof fell on him to demonstrate the debt’s existence in alleging non-payment.

Foundations laid by the French and Spanish in the 18th century survived to shape the course of history in the city. The city plan, the central square overlooked by church and state, French arpents, city lots, faubourgs, heavy trusses, Creole cottages, the old Convent, and Charity Hospital came from the French side. But streetscapes full of repeating arches, Arabesque ironwork, covered passageways, and the still-alluring sense of guarded privacy came from His Catholic Majesty of Spain, not His Christian Majesty of France. If it all sounds confusing and unresolved, we invite your opinion. See you at the café?

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who co-authored the award winning series New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf – An Early History. She is currently working on a social and architectural history of New Orleans public markets and on a book on the contributions of free persons of color to vernacular architecture in antebellum New Orleans.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

French Speaking ‘Hommes de Couleur Libre’ Left Indelible Mark on the Culture and Development of the French Quarter

Top to Bottom: 933 Rue St. Philip, home of builder and community leader, Jean-Louis Dolliole; 1440 Rue Bourbon, another home built in 1819 by Dolliole

Jean-Louis Dolliole, 19th century builder and community leader, was the son of a Provencal Frenchman and Genevieve Laronde, a mother of African heritage. As a French-speaking free person of color or homme de couleur libre, Dolliole played an important role in developing and maintaining the culture and traditions of New Orleans. Serving also as testamentary executor, legal tutor or sponsor for friends and relatives, he helped to maintain the family lives and stature of the free black community. Best known as a talented builder along with his brother Joseph, Dolliole applied his skills to the creation of homes built and framed in the “French-style.” Using local materials like orange-red country brick and wood of cypress or pine, he drew largely on French building methods such as the triangular roof truss, half-timber construction, and the use of shingle, slate, or hook tile roofing or over lathing strips to fashion rooflines. Dolliole’s home in the French Quarter at 933 St. Philip represents the best of vernacular architecture. Built in 1805 and owned by Dolliole for a half century, it was rescued from near ruin by a skilled local architect and his wife, an historian and educator. And steps from Esplanade, Dolliole’s masterpiece at 1440 Bourbon stands on an irregular lot that reflects the crazy-quilt angles of the Faubourg Marigny. Here in 1819, Dolliole assembled the haunting lines of a softly-colored plastered brick cottage with a kaleidoscopic, double-pitched hipped roof of enduring flat tiles. To this day, the house is one of the most picturesque in the city.

Jean-Louis Dolliole was one of thousands of free people of color whose legacies survive in neighborhoods, church life, business, politics, music, writing and Francophone culture. Their records abound in local archives, dating from the 18th century until the Civil War and later. Among important builders were Pablo Cheval, Paul Mandeville, Bazile Dédé, August Philippe, Francois Darby, Charles Dupard, Manuel Moreau, Francois Boisdoré, Louis Barthelemy Rey, the Dollioles, Toby Dominique, Mytille Courcelle, Francois Fils, Florville Foy, Pierre Rillieux, and Joseph Chateau.

Joseph Chateau was one of the most prolific free black builders of the ante bellum period. His work has significance in a number of areas. New Orleans notaries of the 1840s recorded seventeen contracts documenting his building activities. Chateau’s stock-in-trade was the Creole cottage with a façade that was scored or floché to resemble stone, with decorative, red-hued painting. He also worked in other genres, building townhouses, renovating a store on Chartres St., and making innovations to the vernacular cottage. He responded creatively to his clients’ needs, such as getting a workable house built on a extra narrow lot, creating attractive rental property, tweaking space and a deeper footprint out of the traditional gable-sided cottage, and keeping up with fashion trends while preserving tradition. Chateau could also do drafting. While less than one per cent of building contracts have plans attached, over half of his have drawings, mainly floor plans that he executed with sophistication, and several with elevations.

Another profession, one called “merchant tailor,” was a niche and springboard for free men of color. Importing luxurious ells of silk, linen and Belgian Limbourg cloths, they fashioned high-style frock coats, cravats, vests, and pants for fastidious gentlemen, maintaining well-appointed storefronts with numerous employees. Several turned their profits into real estate investments. While still in their thirties Chartres Street merchant tailors Julien Colvis and Joseph Dumas owned 5 houses in the French Quarter, 21 in Tremé, 3 in the Marigny, 11 in the St. Mary Faubourg, and one in the town of Mandeville. On the same street, tailors Etienne Cordeviolle and Julien and Francois Lacroix amassed a fortune, and citywide holdings. Bourbon St. tailor Louis Barthelemy Rey formed a partnership with the land developer Victoria Lecesne. Victoria was wife of a man named Chazal Thomas, but identified her separate property in business dealings. It was not uncommon for free women of color to engage in business or build their own homes. Francoise Fusillé, Marie Laveau, Modest Foucher, Madeline Oger, Charlotte Morand, Rosette Rochon, Eulalie Mandeville, and Helene Toussaint, were among the many who records show built homes or engaged in business.

Today the spiritual heirs of the likes of Jean-Louis Dolliole, and Joseph Chateau celebrate their accomplishments. The old French names live on in their communities. Their legacy lives in the city’s fabric.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who co-authored the award winning series New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf – An Early History. She is currently working on a social and architectural history of New Orleans public markets and on a book on the contributions of free persons of color to vernacular architecture in antebellum New Orleans.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

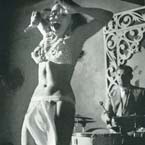

Vintage Bourbon Street Burlesque

New Orleans in the Forties and Fifties was often heralded as “The Most Interesting City in America.” Bourbon Street was its epicenter, and it became world famous for its concentration of nightclub shows featuring exotic dancers, comics, risque singers, and contortionists, backed by live house bands. Along a five-block stretch, over fifty acts could be seen on any given night. The street gleamed with neon lights as barkers enticed tourists and locals into the clubs to see the featured attractions whose photographs were prominently displayed in the large windows outside. Clubs included the 500 Club, the Sho Bar, and the Casino Royale. It was a glamorous street where men and women dressed in their finest to take in a show.

New Orleans has a history of appealing to the carnal senses. Storyville, the famed red-light district at the turn of the last century, was known for its many houses of prostitution as well as being the birthplace of jazz music until it was closed down in 1917. After vaudeville, and the success of burlesque, striptease became a mainstay on the nightclub stages. In the Forties, stripteasers were in it for the money, as servicemen passed in and out of town looking for a good time. But, as “Stormy,” one of the most popular Bourbon Street dancers at the time said in Cabaret magazine, “Anything you do–no matter what it is–if you do it well enough, can be lifted to an art.”

A competition formed between the club owners to see who could draw the biggest crowd and make the most money. Girls competed with each other by creating acts based upon elaborate themes. Imagination was always the key even as props, beautiful costumes, mood lighting, and original music were incorporated into their acts. This only enhanced the natural beauty and talents of the girls. There were a bevy of exotic dancers like Lilly Christine the Cat Girl, Evangeline the Oyster Girl, Alouette Leblanc the Tassel Twirler, Kalantan the Heavenly Body, Rita Alexander the Champagne Girl, Blaze Starr, Linda Brigette, the Cupid Doll, and Tee Tee Red.

The young beauties of Bourbon Street gained star status. They had their own hairstylists, maids, assistants, agents, and managers. They mingled with visiting celebrities. Some exotic dancers were given small roles in films. Lily Christine the Cat Girl graced the cover of dozens of national magazines, and appeared in a few movies. Considered the top attraction on Bourbon Street, she performed at Leon Prima’s 500 Club. Musician Sam Butera, who worked with “the Cat Girl,” recalls her popularity, “One time they had a hurricane threatening. People were standing outside the 500 Club a block long waiting to get in. That’s how popular she was. With a hurricane warning!”

Controlled publicity was a convention of the time on Bourbon Street. Some clubs promoted their stars by putting their images on drinking glasses and postcards. Some of the dancers had drinks named after them. Getting arrested on obscenity was always good for a headline in the newspaper. A few exotics from Bourbon Street staged elaborate catfights or public displays that landed them spreads in LIFE magazine, the most-read magazine in the country at the time. Blaze Starr became quite famous for her affair with Governor Earl Long. The nationwide scandal became the focus of her autobiography, which later became the basis for a major motion picture.

The French Quarter had a seamier side. Pimps, prostitutes, criminals, and mob figures inhabited the Quarter. And B-drinking, in which strippers tempted men to buy them drinks for a cut of the profit, was rampant–and illegal. And, since everyone dressed up to attend a show, the girls often didn’t know if they were sitting next to a wealthy oil man, or an oily thug.

Politicians courted their own doom by enjoying themselves in the clubs, and it was ultimately their undoing that brought down the final curtain on girlie burlesque. During the 1960s, New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison “cleaned up” Bourbon Street. The clubs were raided, and girls were arrested for charges of B-drinking and obscenity. To cut costs, the club owners first got rid of the bands, and replaced them with records. The sexual revolution of the Sixties eventually brought in go-go dancers, porn films, and strippers whose acts focused on flesh more than flash. Top musicians like Al Hirt and Pete Fountain survived, but the great burlesque queens of the 1950s did not.

For show dates and times, visit www.bustoutburlesque.com. Times Picayune theater critic, David Cuthbert says, “‘Bustout Burlesque’ has authenticity, electricity, and lubricity. It’s a fun night out to savor the lost art of the striptease, lovingly re-created and performed by gloriously good-looking girls who are oh, so naughty, but oh, so nice.”

Rick Delaup is a native of New Orleans, and the creator of Eccentric New Orleans and producer of Bustout Burlesque. He graduated from De La Salle High School, and spent a year at L.S.U. in Baton Rouge before going to film school in Chicago. He graduated from Columbia College in 1990 with a B.A. in Communications with a concentration in documentary filmmaking. He is an independent producer on a mission to tell the true, uncensored stories of real New Orleans people.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Still We Rise Again

Images taken by the U.S. Corps of Engineers following Hurricane Betsy 1964

Aged and weathered cities all have their darkest hours, but somehow the ruins get better. Rome is still beautiful and has lived to tell the tale of its sackings by the Gauls, the Goths, the Vandals, the Ostrogoths, the Normans, and even a Renaissance Spanish army. The late Leonard Huber tells us that on the lower Mississippi river, thirty-eight floods occurred between 1735 and 1871 and nine of these inundated New Orleans. A levee break or crevasse in Kenner, he tells us, “brought water as far as Chartres St.” in 1816. The Sauve crevasse in 1849 “flooded 220 squares and drove 12,000 people from their homes.” The great crevasse at Bonnet Carre in 1871 propelled so much water from the river into Lake Pontchartrain that when a north wind blew the water toward the city, the Hagan Avenue levee broke and the city flooded. Still we rose again.

New Orleans has the distinction of flood threat from river, lake, and rainfall. The devastating hurricane of 1915 pounded the town with 120 mph winds, which segued in the next two weeks into 22 inches of downpour. The “Good Friday” rain of 1927 dumped 14 inches in one day while lightning disabled the power train to several pumping stations. The flood that year in the Mississippi Valley propelled the federal government to assume control of the river’s main line levees and install the Bonnet Carre Spillway to protect the city. Forty years later, four Times-Picayune reporters trumpeted in 1964 that New Orleans had not had a major (river) flood in a century, the year before Hurricane Betsy hurled 150 mph winds over the city, sinking ships in the river and topping the levees in the lower city and St. Bernard Parish. Although seven feet of lake water covered these areas, they still rebounded.

Disease, fire and mayhem?

If floods haven’t killed us, what about disease, fire, and mayhem? Again, Huber tells us that yellow fever struck twenty-three times before 1860, killing some 30,000 citizens. Asiatic cholera, especially in the 1830s, sent souls to their maker at a rate of nearly a thousand a month for a two-year period. People were buried in trenches, entire families taken, and carts for the dead piled high and in as short supply as housing in the flood zone. Four-fifths of the city–including the provision warehouses–burnt to the ground in 1788, leaving the citizens homeless and hungry. When the Irish merchant and American patriot Oliver Pollock delivered a shipload of flour and medicine to the city at regular prices, Governor Esteban Miro was so grateful he gave him a trading monopoly. Pollock later bought Elmwood Plantation with his business profits.

Those who count the Katrina aftermath as our darkest hour might consider 1794, when a hurricane struck on August 10, another brought rain and flood on the 21st, and the city (then just the French Quarter) burned a second time on December 8, followed by looting. Governor Carondelet faced the desolation without FEMA to blame or complain about and without America coming to the rescue with troops and billions of dollars. But the city rose again.

Our founders were not unaware of the “topographical challenges” to their early settlement. But at fourteen feet above sea level, with a ridge of land along Bayou Sauvage connecting it to the lake and thence to the Gulf of Mexico, the site of the Vieux Carre looked promising in 1718. All things being relative of course, it was promising in contrast with the cypress swamps that surrounded it, giving rise to 19th century street names like Marais (swamp, quagmire), the old name for the modern street alongside the Superdome. Need we say more about that? Accordingly, the first suburbs clung to the river, the Faubourgs St. Marie (1788) and Marigny (1806) being only seven to ten blocks deep as late as 1850. As the city grew upriver and the plantations one by one began to subdivide, they drew their rear lines at about Freret St.–the present uptown border of Katrina’s infamous crusty brown water line.

Technology, topography or human willfulness and spirit

Technological progress in the 20th century for the first time made all 200 square miles in the city limits “inhabitable,” including the Ninth Ward. The formidable A. Baldwin Wood pumping system went on line in 1908, after which the city’s growth was “freed” of its topographical limitations. Citizens now refer to “The Pumps” like benign relatives, like a set of uncles looking after us. It is well to note that it was not the pumps that failed us this time. The recent disaster still tested the assumptions of the 20th century, leaving those of earlier periods undamaged.

The issue now is whether the community should rely on engineering, topography, or the human ability to rise from the ashes whatever the catastrophe. If we follow the example of our forebears, the answer is obvious–build raised houses behind levees on higher ground and expect the next disaster. A favorite local icon is the sight of a ship riding in the river about twenty feet above the street leading to it. It reminds us that we live with danger. And we know we will rise again.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who co-authored the award winning series New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf – An Early History. She is currently working on a social and architectural history of New Orleans public markets and on a book on the contributions of free persons of color to vernacular architecture in antebellum New Orleans.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

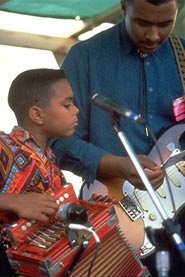

Rubbing the Right Way: The Infectious Sounds and Long Evolution of Zydeco Music

Louisiana Zydeco Musicians

It’s Thursday night at the Mid-City Lanes Rock ‘n’ Bowl (4133 S. Carrollton Ave., 504-482-3133), a vintage, second-floor bowling alley located near the geographic center of New Orleans. Bowlers are rolling strikes and gutter balls on the lanes, but the attention of most in the crowd tonight is focused on the stage. Thursday is zydeco night at Rock ‘n’ Bowl – which also functions as a music hall – and most of the people have come to dance. In a moment, the accordion, rubboard, drums and guitar ring from the stage, the singer begins hollering a mixture of Creole French and English lyrics about love and loss and the wooden floor fills once again with dancing couples.

Zydeco is as distinctive a component of Louisiana culture as crawfish, hot sauce and bayou landscapes, and like many things Louisianan, its colorful traditions and intricate history lend it a distinctive style among other genres of music.

At its essence, zydeco is the dance music of the black Creoles of southwest Louisiana and east Texas, says Michael Tisserand, whose book “The Kingdom of Zydeco” tells the story of the music and the communities that produced it. Though it started in the swampy bayou lands in the early part of the 20th century, it has exploded in popularity in the past few decades. It’s common to find zydeco festivals in California and the Northeast and Louisiana bands can now tour the world with their music.

“The reason for its enduring popularity at local dancehalls and at stages everywhere else is pretty obvious – it’s hard to stand still when you’re hearing great zydeco,” says Tisserand.

Sure enough, wherever a zydeco band is performing, feet begin moving, bodies begin swaying and couples come together for fast-paced dancing or slow-tempo waltzes. There is a dancing style universally called zydeco dancing, but the music is so infectious that people hearing it for the first time are often drawn to the dance floor to do their own thing.

Cajun or Zydeco?

One common point of confusion for visitors and new initiates to zydeco music is its relationship to Cajun music. Just as Cajun and Creole cooking are often equated, so too are Cajun music and zydeco often mistaken as two different names for the same thing. Like the cuisines, they do share much in common – most importantly the accordion that is so prominent in each genre – but each developed under its own set of influences and have unique sounds and styles. Cajun music comes primarily from the traditions of the French-speaking Cajuns who came to Louisiana from modern-day Nova Scotia, while zydeco music reflects the African-Caribbean roots of its players, Tisserand explains. The fiddle turns up in Cajun music while the rubboard (that corrugated metal plate that looks like an old fashioned laundry device) is a lead sound in zydeco. And while Cajun music has incorporated more stylings from country music, zydeco has picked up more of its own contemporary influences from blues and R&B.

“The histories of the two styles of music are deeply intertwined, and there are Cajun musicians who play zydeco, and zydeco musicians who play Cajun. Basically, you just can’t tell a musician what they can and can’t play,” Tisserand says. “Face it, it’s Louisiana, and everything’s all mixed up together in the most wonderful of ways.”

The word “zydeco” has its own colorful history. It is derived from les haricots, French for beans. One commonly cited explanation for the evolution of the word goes back to a Creole expression: “les haricots sont pas sales,” or “the beans aren’t salty” – a reference to hard times when families could not afford salted meat to season their beans. One of the first recognized zydeco artists was Amede Ardoin, who made numerous recordings in the late 1920s and 1930s, setting the standard for generations to come. His own family legacy provided plenty of its own zydeco history along the way, and now his descendants Sean Ardoin and Chris Ardoin both front Lake Charles-based bands that often visit New Orleans. Clifton Chenier took the mantle of “king of zydeco” and during the 1950s and ’60s blended in R&B and rock sounds for a more swinging evolution of zydeco. The styles of today’s players now span from traditionalists like Boozoo Chavis to wide-ranging and flamboyant Buckwheat Zydeco.

Finding Zydeco

Because zydeco is so strongly associated with the culture of south Louisiana, visitors to New Orleans are often surprised to find that relatively few clubs offer live zydeco music on a regular basis. Jazz, New Orleans-style brass bands, blues, rock and funk are much more prevalent in the city than either zydeco or Cajun music. That’s because most zydeco musicians come from southwestern Louisiana and east Texas – from the communities in and around Lafayette, Lake Charles and Houston – and when they aren’t touring the country or abroad tend to play closer to home.

But visitors usually stand a good chance of finding some live zydeco on any given night in New Orleans. The richest local harvest of zydeco comes when a New Orleans music festival is taking place – especially the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival (www.nojazzfest.com), the French Quarter Festival (www.fqfi.org) – both held in the spring – and the Swamp Fest (www.auduboninstitute.org), held Uptown in the fall. Year-round, the most reliable venue to find zydeco in New Orleans is Mid-City Lanes Rock ‘n’ Bowl, an inviting venue for local regulars and visitors alike where some of the top names in zydeco hold court on the stage. In the French Quarter, some clubs on Bourbon Street periodically host zydeco acts, especially the Old Opera House (601 Bourbon St., 504-522-3265), where Dwayne Dopsie and the Hellraisers frequently play when they are not touring. Also, Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes – the one-time Kansas City Chiefs pro football player – plays a blend of zydeco, Caribbean and blues music with his band Sunpie and the Louisiana Sunspots. They regularly perform at venues around New Orleans, where Barnes also works as a ranger at the National Park Service’s French Quarter unit (419 Decatur St., 504-589-4841).

For recorded zydeco, check out the extensive selection of CDs at the Louisiana Music Factory (210 Decatur St., 504-586-1094).

Ian McNulty is a freelance food writer and columnist, a frequent commentator on the New Orleans entertainment talk show “Steppin’ Out” and editor of the guidebook “Hungry? Thirsty? New Orleans.”

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Faubourgs Tremé and Marigny Are French Quarter Neighbors Rich in History and Architecture

Top two Faubourg Marigny images by Alexey Sergeev, bottom image courtesy Louisiana Department of Culture Recreation and Tourism

The historic Faubourgs Marigny and Tremé sit just beyond the French Quarter like old Parisian quartiers. Faubourg, literally “false town,” is the traditional French word for a suburb outside the walls of the city, still governed by the larger metropolis. Fashionable Esplanade Avenue, once the city commons, is the dividing line between the French Quarter and Marigny and between Marigny and Tremé, while the “Street of the Fortifications” or Rue des Remparts–now Rampart–divides the Vieux Carré from the Faubourg Tremé.

Both New Orleans neighborhoods were born at the turn the 19th century. Bernard Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville inherited his father’s plantation just below the city gates in 1800 at the age of 15. On reaching his majority six years later he at once had it subdivided. Marigny’s development was immediately popular. He spent most of 1806 and 1807 at the office of notary Narcisse Broutin selling sixty-foot lots or emplacements to prospective homebuilders. On the Rampart side of the French Quarter, Claude Tremé by marriage and inheritance came into possession of an ancient tilery and brickyard dating to the early French colonial period. The principal residence on it dated to the 1720s. By 1800 Tremé had begun to subdivide and sell the property. In 1810 the city of New Orleans acquired the remainder and resold the lots to residential buyers.

It was in these village-like settings that French-speaking free people of color, working class whites, and immigrants settled in the Ante Bellum period. On crooked extensions of French Quarter streets like Bourbon and Chartres, Dauphine and Royal, they placed their cottages close to the banquettes or sidewalks, the high slate rooftops reflecting the city’s heritage of French-style framing. Creole cottages and long, narrow “shotgun” houses still dot the streets of the Faubourgs, along with an occasional bungalow, and in Marigny, a few large warehouses close to the river.

On the zigzag extension of Bourbon St. as it enters the Marigny from Esplanade Avenue, free man of color and builder Jean Louis Dolliole in 1819 began a cottage for his mother-in-law. He placed it at the angle where the street changed its name to “Bagatelle,” now Pauger. The pie-shaped lot carved into the point of the pentagon formed by the streets there had a telling effect on his rooftop. Its curious slopes and the rooftop “pan” tiles are well worth a photo–if you can see through the trees on the banquette. Across the street is another attractive “house in the bend of Bourbon Street.” Built in the 1820s, it features the neighborhood’s first known center hall residence, a narrow, almost timid departure from the prevailing custom of building hall-less cottages.

An open square made a focal and meeting point for each community. Tremé’s fabled Congo Square, where African songs and drumbeats attracted both slave and free populations for Sunday dancing, is now renamed at Rampart and St. Peter St. Families gathered at Washington Square in Marigny to stroll their babies in carriages, picnic, and listen to parade music. The spires of numerous nearby Catholic churches such as Tremé’s handsome St. Augustine and Sts. Peter and Paul in the Marigny attest to the faith of Creole society, both white and African-American. They also catered to the immigrant populations of French, Irish and German Catholics who found their way to the Faubourgs where families could afford to rent one side of a double cottage.

By the 1840s the Faubourgs were bustling with the sights and sounds of working class neighborhoods. The turreted Tremé Market straddled Basin St., extending along the blocks from Marais to North Robertson. The “grim and brooding” 1833 Parish Prison looked down on the market, its pair of fanciful turreted towers belying their watchful purposes. Basin Street, named for turning basin of the old Spanish Carondelet Canal, was home to factories and lumber mills surrounding the basin where sloops and luggers deposited the pitch and tar and lumber derived from piney Northshore forests. The old French families of the neighborhood buried their dead in the above-ground tombs of St. Louis I and II cemeteries, following the burial customs of their ancestors.

Down the middle of the Faubourg Marigny the pioneering steam train that citizens dubbed the “Smokey Mary” departed from its station near the riverfront’s 1840 Port Market. It chugged its way down the neutral ground or median of Elysian Fields Avenue, formed from the right of way of an old sawmill canal that led to Gentilly and Lake Pontchartrain. The massive plantation house of the Marignys, built in the Spanish period between Elysian Fields and Marigny St., remained in place until the 1830s, its former par terre garden replaced by multi-level commercial buildings. Meanwhile, the old colonial residence belonging to the Tremé brickyard survived until 1926, first as the home of a state run college and later as the motherhouse of the local Order of Notre Dame of Mount Carmel.

By 1900 the glittering age of jazz and Storyville dominated the Tremé and adjacent French Quarter neighborhood. This gave way in the Great Depression to the construction of a housing project in the heart of the former Storyville. By the middle twentieth century, “social mobility,” the departure of the old working class families to the suburbs, age and deterioration led to neglect and crime in the old Faubourgs. When the city determined to demolish the historic cottages of nine whole squares of the Tremé, the handful of residents and historians who knew enough to oppose it were powerless.

Change arrived in the 1970s, as citizens began to appreciate what the old Faubourgs meant to New Orleans. Within a couple of decades, both received a spate of new investments, historic zoning, and design review and demolition controls. While the preservation of neighborhoods is a constant battle, and the Tremé neighborhood continues to struggle with crime and poverty, the bright new colors, jewel-box gardens, and rooftops repaired after Hurricane Katrina promise a brand new century of neighborhood living in the Faubourgs.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who co-authored the award winning series New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf – An Early History. She is currently working on a social and architectural history of New Orleans public markets and on a book on the contributions of free persons of color to vernacular architecture in antebellum New Orleans.