Jambalaya and a Crawfish Pie and File Gumbo: Louisiana Seafood Festival is Back

Photo courtesy of Louisiana Seafood Festival on Facebook

Fall in New Orleans means milder temps that are perfect for outdoor events, and that usually means a robust October festival lineup. One of the month’s highlights is the annual Louisiana Seafood Festival — three days of food music held Friday through Sunday, October 27-29. The dates this year are new, and so is the location. The festival will be held in Woldenberg Park, from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. on Friday and Saturday, and from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. on Sunday. The park is located in downtown New Orleans at 1 Canal Street, along the Mississippi River waterfront.

Louisiana’s rich culinary heritage is worth celebrating over and over, and the state’s relationship with seafood has been a huge part of it for centuries. It’s no wonder that the attendance numbers for this fest had been solid, and some of Louisiana’s best restaurants, food popups and catering businesses count themselves among the vendors year after year.

So, skip breakfast and head to the riverfront: Gulf fish, crab, oysters, crawfish, and shrimp await (with some alligator thrown in), prepared in many authentic, mouth-watering ways. Vendors this year include such top local restaurants as Ajun Cajun, Drago’s, Galatoire’s, Jacques-Imo’s, Luke, Mahony’s, Superior Seafood, and Tujaque’s. The Lafitte, LA-based Voleo’s Seafood Restaurant will also be there.

As in previous years, top Louisiana chefs will host cooking demonstrations in the Cooking Pavilion so you could see firsthand how some of the most exquisite authentic Louisiana seafood dishes are prepared. The Kids Pavilion will have seafood-themed activities for the little ones. The Art Village will again feature a variety of local vendors selling art, crafts, jewelry, textiles, and more.

There will be live music starting at 11 a.m. on all three days and ending at 9 p.m. on Friday and Saturday, and 7 p.m. on Sunday. The stellar lineup doesn’t get more Louisiana, and includes Tab Benoit, Bucktown All-Stars, Rockin’ Dopsie Jr. & The Zydeco Twisters, Bonerama, Soul Rebels, and Gal Holiday & The Honky Tonk Revue.

Admission at the entrance is $10 for each day; admission for children under 12 is free. You can also buy tickets online, including single-day passes and VIP tickets ($65, comes with a T-shirt). VIP access includes VIP tent, open bar, private restroom, and front-of-stage viewing area. Weekend passes are $25 for one day and $190 for the whole weekend.

The festival will be held rain or shine. Please note that no pets and hard-sided ice chest are allowed on festival grounds, but chairs, blankets and soft-sided coolers are welcome. There will be ATMs on site too but you may want to bring cash to the festival to avoid the fees and the lines. Most food and beverage vendors will accept cash only, with few exceptions.

There will be bike racks at the entrance to the grounds. Since there is no public parking for this festival parking options will be limited to paid lots and street parking, so consider biking or taking public transportation. The festival is produced as an annual fundraiser by Louisiana Hospitality Foundation, a nonprofit that supports education, health and social welfare.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Over-the-top Gravesites in New Orleans

Italian Benevolent Society Tomb, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA—photo by traveljunction on Flickr

From Ernie K-Doe to the fictional Ignatius P. Reilly, many over-the-top personalities comprise the city of New Orleans. Not surprisingly, these larger-than-life characters often take their showmanship and swagger to the grave. The Crescent City’s above-ground cemeteries offer the perfect vehicle for showing off even after shuffling off the mortal coil. Here are just a few extravagant graves—and where to find them. To schedule a tour at St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, visit cemeterytourneworleans.com.

Italian Benevolent Society Tomb, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1

At the time of its construction in 1927, this mausoleum was one of the most expensive society tombs ever built. (It cost $40,000, which incidentally is the same price Nicolas Cage paid for his pyramid-shaped tomb in the same cemetery in 2009). The elaborate Baroque tomb features 24 vaults and carved marble statues, and it became the setting for a scandalous scene in the 1969 movie Easy Rider.

Nicolas Cage (1964—), St. Louis Cemetery No. 1

Is it the fact that the white, pyramid-shaped tomb contrasts sharply with the surrounding mausoleums and society tombs? Is it the constant presence of red lipstick kisses on its exterior, left by adoring fans? Maybe it’s the Latin phrase inscribed over the entry: “Omnia Ab Uno” (all from one). Or maybe it’s the fact that the celebrity owner of this extravagant tomb isn’t even dead yet. For whatever reason, Nicolas Cage’s future tomb is definitely over the top.

Marie Laveau (1801-1881), St. Louis Cemetery No. 1

Voodoo queen Marie Laveau’s Greek Revival tomb is relatively humble compared to others in the St. Louis Cemetery. Its larger-than-life qualities come from the personality of its occupant. Many supplicants believe Laveau continues her healing magic from beyond the grave, and they leave small tokens, often in sets of threes, as entreaties. Others believe her spirit haunts the graveyard. Whatever your belief may be when it comes to the afterlife, Marie Laveau has transcended death—or her reputation has, at the very least.

Chapel, St. Roch Cemetery No. 1

Head to the rear of this active cemetery, where you’ll find a small Gothic Revival chapel with a crumbling, petite side room filled with prosthetic limbs, crutches, glass eyes, votives and thank-you notes to St. Roch, the patron saint of miraculous cures. The collection of cast-off medical artifacts is creepy or inspiring, depending on your perspective.

Not in New Orleans, but close

Al Copeland, 1944-2008, Metairie Cemetery

Many New Orleanians have fond childhood memories of visiting Al Copeland’s Metairie abode, which he decorated extravagantly during the holiday season. Today, the Popeye’s Chicken founder is interred in an opulent family tomb in Metairie Cemetery. Flanked by urns, white marble columns and a stained-glass door, it looks less like a mausoleum than a minor Greek acropolis.

Chapman H. Hyams, 1838-1923, Metairie Cemetery

How can you be sure that your death causes angels themselves to weep? Commission a marble version yourself, as did millionaire stockbroker Chapman H. Hyams. His “Angel of Grief” statue rests inside a granite Greek temple surrounded by Ionic columns. Stained glass windows illuminate the grieving seraph.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Historic New Orleans Collection Presents Storyville: Madams and Music

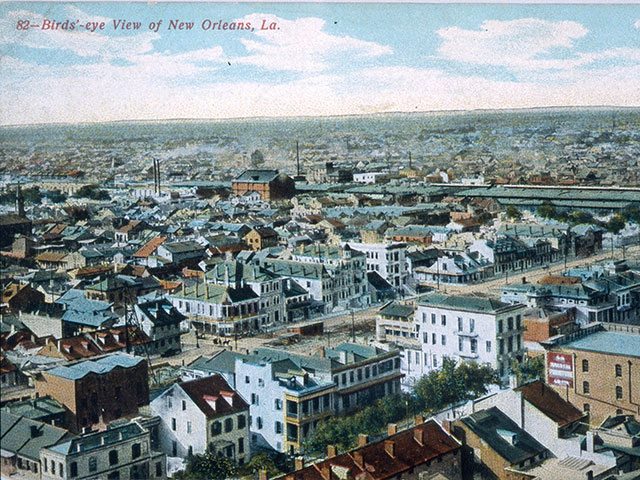

Postcard showing view of Storyville courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Many know Storyville as the red light district where prostitution and jazz music flourished in New Orleans from 1895 to 1917. A lineage of musical geniuses, including Jelly Roll Morton, Buddy Bolden and Pops Foster, gave birth to jazz while entertaining customers at brothels—or so the story goes.

Beyond Basin Street

But a recent talk at the Historic New Orleans Collection by Kansas University professor of American Studies Sherrie Tucker, “More to the Story: Listening for Early New Orleans Jazzwomen,” explored the limitations of this popular narrative. Though it became the dominant explanation of jazz’s origin when the musical form was being institutionalized in universities, the narrative “leaves out a lot,” Tucker said.

Music did not happen in a vacuum, said Tucker, who described herself as “a feminist jazz researcher since before it was cool.” Jazz happened inside and outside brothels, at parties and at homes—and many jazz musicians were women. Their influence on jazz, though mostly unwritten, is undeniable.

The Early Influences of Jelly Roll Morton

Though Jelly Roll Morton is the greatest legend of Storyville, he might never have come to prominence without the influence of a woman. Mamie Desdunes, a pianist who played in Storyville brothels, was one of Morton’s teachers. Morton gave credit to Desdunes in Mamie’s Blues and admitted it was Desdunes who taught him what he called “the Latin tinge.” “She played the blues like this,” he said on one recording before launching into a habanero rhythm.

Morton also described Desdunes in an oral history recording.

“Among the first blues that I’ve ever heard, happened to be a woman, that lived next door to my godmother’s in the Garden District,” Morton said. “Her name was Mamie Desdunes. … So she played a blues like this all day long, when she first would get up in the morning.”

Sadly, Desdunes died in 1911, at age 32, leaving behind not a single recording of her music. But her influence can still be heard in Morton’s many surviving records.

Women Bandleaders

The daughter of two trumpet players, Dolly Dureaux Adams began playing gigs at parties with her older brother and uncle when she was just nine years old. Her fifty-year career as a pianist and bandleader led her to play with jazz greats, including Kid Ory, Louis Armstrong and Joe “King Oliver.”

Emma “Sweet Emma” Barrett (1897-1983) was a self-taught pianist, vocalist and bandleader who maintained a 25-year gig at Preservation Hall. She made her first recording for Columbia Records in 1926 and played her last gig in 1983, ten days before she died.

”Emma’s role was to keep the rhythm and beat going,” said William Russell, a Tulane archivist, in her obituary in the New York Times. ”For such a small lady, she had tremendous power. She sat on a low stool and in her later years, a wheelchair with her hands higher than her arms, yet she got all that power in there.”

This tremendous power—both Barrett’s and that of other jazz woman—continues to resonate around the world. This is just a sampling of the female jazz greats. Though their stories remain little known, their music lives on.

To learn more about women and the history of jazz, visit the Historic New Orleans Collection’s Williams Research Center (410 Chartres St.), which hosts an exhibit titled Storyville: Madams and Music through November 2018.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Red Hot Burlesque Shows in New Orleans

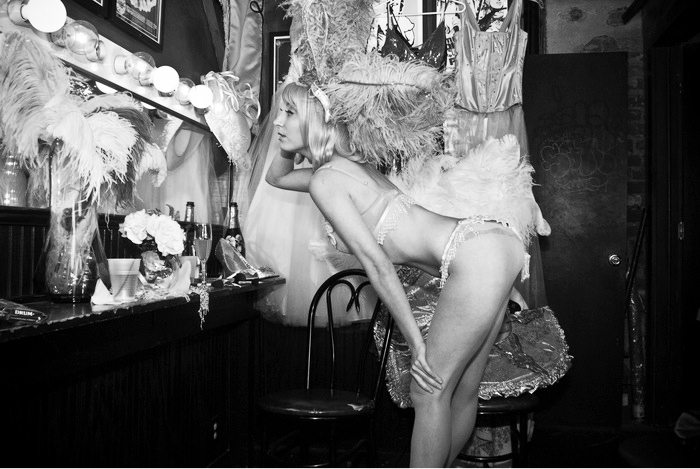

Roxie Le Rouge’s Grand Hotel – A Burlesque Theater Experience – Photo by Roy Guste

We’re at a stage in the New Orleans neo-burlesque revival where you can catch a bit of corset on almost any night of the week in the Crescent City. And that supply of garters and g-strings and cheeky humor wouldn’t come without a massive demand. Where does this market originate?

If you ask us, it’s not just a matter of visitors and locals wanting a bit of noir and naughtiness. Rather, we’d argue that the burlesque renaissance that has swept America has found particular purchase in New Orleans, a city that fits the art of burlesque like a long satin glove just waiting to be playfully tossed aside to the wings of a red-lit stage.

Trixie Minx – Photo by Jian Bastille

It would be impossible to discuss burlesque in New Orleans without mentioning Trixie Minx and the Fleur de Tease burlesque revue. In a city like New Orleans, where there are literally hundreds of regular live acts anchoring the local calendar, it’s an accomplishment to be a blue chip performance. All the more so given that the city’s most famous repeated gigs tend to focus on music, as opposed to the variety show approach of Fleur de Tease.

Which, let’s be fair does include music – as well as magic acts, comedy, circus acts, aerialists, and of course, plenty of burlesque dancers. The Fleur de Tease show has become a fixture of the city’s entertainment calendar, and should not be missed – catch a show at One Eyed Jacks.

Miss Minx also promotes beloved burlesque shows like the Burlesque Ballroom, which features live music backing and pops off at the Royal Sonesta Hotel; Burgundy Burlesque, a self-described revue for ‘high-end glamorous’ burlesque at The Saint Hotel; and Bourbon Boylesque at Oz, a show aimed at the gay crowd and the more explicitly LGBT blocks of Bourbon St.

Burlesque Show at One Eyed Jacks – Photo by Photo by Roy Guste

The Ballroom and Burgundy Burlesque shows are notable for their use of backing live jazz bands, a hearkening back to the old roots of New Orleans burlesque, when the shows and jazz music were seen as equally risque. That relationship of shared sinfulness speaks to the importance of burlesque to New Orleans history – and vice versa. As one might guess, the city has a seminal place in the story of this performance art. While the Crescent City didn’t invent burlesque, New Orleans both expanded on the genre, popularized it, and in many ways, mainstreamed it.

The roots of burlesque can be traced to early 20th century vaudeville, with its sketch show-esque panoply of multiple-act entertainment, which eventually began to incorporate elements of racy strip tease (the removal of clothes sometimes ‘covered up’ – an ironic term in this content – for the relative lack of skill for early burlesque dancers). When burlesque made its way from the gin joints and booze halls of New York and Chicago to the neon strip of 1940s Bourbon Street, an art form had found the perfect, muddy soil for sprouting.

New Orleans, after all, had both the music grounding to provide an excellent sonic backup to burlesque acts, coupled with a sin city reputation that allowed for behavioral envelope pushing. At the time, Bourbon St had only recently become the epicenter of bad behavior in New Orleans, which had shifted from the shuttered Red Light district of Storyville.

Live music, neon lights and folks looking to misbehave pushed the business growth of burlesque; New Orleans’ native talent for showmanship pushed, shall we say, the performance’s brand growth. Famous burlesque dancers were soon attended by entourages of makeup artists, backup singers and dancers, managers, club owners and personal stylists. The most famous burlesque dancers had the name recognition of the most famous local musicians; dancer Blaze Starr would become a well-known mistress of Governor Huey Long.

Local New Orleans burlesque clubs were raided in the 1960s, effectively driving the art form out of the city (the burlesque clubs and revues were ironically replaced by more aggressive strip clubs). And that was the fate of the art form in this city for decades, until the advent of Hurricane Katrina.

Roxie Le Rouge – Photo by Roy Guste

In that storm’s aftermath, performers like Trixie Minx began the process of resurrecting burlesque into a sort of millennial renaissance. What we find fascinating is the way burlesque’s twin peaks of popularity in the city reflect two different – yet somehow similar – eras of New Orleans vice. In both periods, burlesque has been about music, wry observation, satire and straight-up stage presence. But in the 21st century, elements and themes of feminism, female sexuality, body acceptance, and empowerment have also taken center stage, as it were.

Here are some more of our favorite burlesque shows in the city:

The Allways Lounge The Allways, besides being a great bar, is a live entertainment venue where you may see swing dancing, experimental sound orchestra a la a millennial John Cage, live comedy, drag queen trivia and yes, a fair bit of burlesque.

Siberia Conveniently located across the street from the Allways Lounge (the street, in this case, being St Claude Avenue, on the edge of Faubourg Marigny), Siberia regularly features punk rock, bounce shows, and plenty of burlesque revues. This spot also has a kitchen dishing out Eastern European grub, which goes great with a bit of neo-noir cabaret.

Bustout Burlesque Another French Quarter classic, Bad Girls of Burlesque perform regular engagements full of spectacle and sheer colorful panoply at the House of Blues. This is one of those regular New Orleans engagements you don’t want to miss.

Sobou Not just one of our favorite restaurants in the French Quarter, Sobou also accentuates its Sunday Creole cuisine brunch with a bit of burlesque courtesy of the incomparable Bella Blue.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Real Thing: Jazz Shows in the French Quarter

NOLA Snug Tomcats 2 by Infrogmation of New Orleans

Jazz lives in New Orleans, and it comes out to play in the French Quarter.

Every night in the Quarter, old masters and young lions take to the stage to continue the city’s rich jazz traditions and guide the music’s future. Below, we visit some of the top establishments in and near the French Quarter where guests can get close to this living heritage. Some are generations-old stalwarts, while others are so new they’ve barely had their paint scratched.

The name of Fritzel’s European Jazz Club (733 Bourbon St., 504-561-0432) may sound continental, but the music scene at this intimate Bourbon Street club is all New Orleans. Traditional jazz is presented nightly by local musicians as well as by bands visiting from Europe. A few short steps in from the bustle of Bourbon Street, and guests are sitting practically knee-to-knee with gracious Dixieland performers.

Closer to the river, the Palm Court Jazz Café (1204 Decatur St., 504-525-0200) is a classy showcase for traditional jazz, featuring many of the city’s masters as well as members of the next few generations carrying the torch. The wall of windows, tiled floor and bentwood chairs all set the scene for this classic music hall, located just a block up from the French Market and the riverfront itself. An extensive menu of Creole food from their capable kitchen provides the makings for a full night.

The fabled Preservation Hall (726 St. Peters St., 504-522-2841) isn’t so much a music club as it is a living museum to traditional New Orleans jazz with only one exhibit: the band. Don’t look for a bar, reclining seats or even air conditioning in this evocative and character-soaked performance space. The building itself dates back to the 1750s, and it has alternately served as a home, a tavern, an art gallery and an informal rehearsal space. The present owner’s parents, Allan and Sandra Jaffe, purchased the building in 1961 and opened it as a venue dedicated to keeping local jazz traditions alive. Judging by the lines of eager guests for the nightly shows, that’s one mission accomplished.

Located on rollicking Frenchmen Street just outside the Quarter, Snug Harbor Jazz Club (626 Frenchmen St., 504-949-0696) has for years retained the title of New Orleans’ premier venue for contemporary and traditional jazz. Audiences enjoy a refined and upscale setting, seated at small, candle-lit tables, to savor the music of top local and touring performers. Celebrity sightings are frequent and the bistro just outside the performance space offers many Creole favorites.

Across the street, the Spotted Cat (623 Frenchmen St., 504-943-3887) is a relative newcomer to the music scene, but this cozy and intimate former storefront has quickly established its niche as a venue for up-and-coming local performers. A stage built right into a bay window and free admission encourage many curious guests to wander inside for an earful or even to take a spin around the matchbook-sized dance floor. The come-as-you-are vibe and nostalgic bands perfectly recapture the sounds and mood of a bygone era. Another, less sweaty (but still fun) branch of the Cat has opened at the Healing Center, deeper in the Marigny, on St Claude Avenue.

Also on St Claude, Sweet Lorraine’s (1931 St Claude Ave; 504-945-9654) has a modern interior that’s frankly a bit of a jolt after hanging out in tiny, ramshackle gig spots. This is a popular hangout for members of Social Aid & Pleasure Clubs (local African American civic societies), and is well known as the kick off spot for the Black Men of Labor Second Line. Call ahead to check for showtimes, and order some food – the kitchen here works some fine magic.

The Treme can rightly be considered the birthplace of jazz, and as such, many jazz fanatics consider a show here a major New Orleans bucket list item. The Candlelight Lounge (925 N Robertson St) has started welcoming tourists on a larger scale, and the clientele divide – between locals and visitors – sometimes feels pronounced. But the music that kicks off here is undeniably enjoyable.

It’s a bit impossible to miss Kermit’s Treme Mother in Law Lounge (1000 N Claiborne Ave; 504-814-1819) the synthesis of the vision of two iconoclastic New Orleans musicians. The original Mother in Law Lounge was founded by Ernie K-Doe, who penned the eponymous R&B hit and also proclaimed himself Ruler of the Universe (why? Because New Orleans). Local trumpet virtuoso Kermit Ruffins has since taken over this brightly painted bar, which beckons visitors with its giant murals and excellent live shows.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Brennan Family: A Luscious Legacy

Top to Bottom: Brennan’s Restaurant; Bacco Restaurant; Palace Cafe; Dickie Brennan’s Steakhouse; Dickie Brennan’s Bourbon House

New Orleans is famous for its Creole interpretation of French cuisine, but one of the most famous names in the New Orleans culinary scene is neither French nor Creole. The Brennan family, of Irish descent, is nonetheless responsible for fostering a culinary tradition that many regard as the epitome of New Orleans fine dining.

Separate branches of the Brennan family today operate 13 restaurants, of which 10 are located in New Orleans and seven in the French Quarter proper or its periphery. This is not the sprawling restaurant empire it might seem at first blush, but rather an enduring legacy for a local family and their business partners who own and operate one or more of these restaurants independently of each other. Indeed, a stroll of only three blocks in the French Quarter will take a pedestrian past five high-profile restaurants owned by four different scions of the extended Brennan family.

The family’s rise in the restaurant business began in grand fashion in 1946 when a bar owner named Owen Edward Brennan opened a French restaurant on Bourbon Street. Brennan’s Restaurant (417 Royal St., 504-525-9711) moved to its present location in 1956, occupying a Vieux Carre building that dates back to 1795. From the start, Brennan’s was the kind of place that captured the imagination and it quickly attracted a regular clientele of international movie stars and local dealmakers. Though anchored in the classics, the kitchen at Brennan’s innovated and is responsible for many dishes that are today regarded as New Orleans classics, most notably bananas Foster. Following an extensive renovation, the new Brennan’s balances its status as a stalwart of Creole traditions and an innovator of New Orleans cuisine.

By the 1970s, other members of the Brennan family had taken over Commander’s Palace (1403 Washington Ave., 504-899-8221), which had been operated as a restaurant in the upscale Garden District neighborhood since 1880. The careers of world-famous chefs Emeril Lagasse and Paul Prudhomme were each launched at the kitchen of Commander’s Palace under Brennan management in the 1980s, and today the restaurant remains one of the city’s most popular upscale dining destinations.

The ongoing success and renown of these Brennan-owned restaurants became the springboard for members of the extended family to open their own, which now cover a remarkably diverse culinary range from traditional Creole to Italian fare to American steakhouse standards. Family members continue to open new restaurants, with two coming online within the last few years in New Orleans, and Brennan-branded restaurants are now in business in Houston, Las Vegas and Anaheim, Calif.

What follows is a primer to the Brennan-owned restaurants in the French Quarter and other New Orleans neighborhoods:

Mr. B’s Bistro (201 Royal St., 504-523-2078) took much of the fussiness out of high-end dining when it opened in 1979, and infused the dining scene with many innovations which are still widely imitated to this day. Polished but not formal, the bistro’s semi-open kitchen introduced a new trend in restaurant design, while its menu broke ground with dishes that are now industry standards, such hickory-grilled fish. The restaurant’s dark and smoky “gumbo yaya” is widely regarded as one of the city’s best versions of this Louisiana classic.

Palace Café (605 Canal St., 504-523-1661) was opened by Dickie Brennan in the same year his cousin opened Bacco a few blocks away. The building the Creole bistro now operates in, however, has a history that reaches back to 1905 when it was the home of Werlein’s for Music, the nation’s oldest retail music business continually owned by the same family. In the old days, the progenitors of jazz and later musical genres bought sheet music and instruments here. Today, after an extensive renovation with many memorials to the building’s musical past, guests dine on Creole food that blends tradition with innovation. Sunday jazz brunch is a standard feature here and during Mardi Gras season the bistro’s broad second-floor windows offer great parade viewing on Canal Street.

Ralph Brennan’s Red Fish Grill (115 Bourbon St., 504-598-1200) is the most casual of any Brennan-owned restaurant located in New Orleans, perhaps befitting its Bourbon Street address. Opened in 1997, the restaurant’s interior has a colorful and playful aquatic look and the menu is focused on Gulf Coast seafood. Lunch can be as simple as po-boys and burgers while also featuring many of the fresh fish preparations offered on the more elaborate dinner menu. A long, cool oyster bar serves up local bivalves raw or baked with savory toppings.

Dickie Brennan’s Steakhouse (716 Iberville St., 504-522-2467), opened in 1998, continues a long tradition of steakhouses in New Orleans, where the style of serving steaks sizzling aromatically in butter first gained fame. The distinctly masculine dining rooms here are sunken below street level, a rarity in low-lying New Orleans, and offer an urbane elegance. Steaks are all prime and are served either with a light seasoning or dressed up with decadently rich sauces, fried oysters and other indulgences.

Dickie Brennan’s Bourbon House (144 Bourbon St., 504-522-0111) does indeed stock a prodigious selection of bourbons, but the four-year-old restaurant is better known for its seafood, particularly the raw oysters served at its crescent-shaped oyster bar or those included in the giant “plateaux de fruits de mer,” a collection of cold seafood served for two or up to eight people. In addition to its bistro-style dining rooms, Bourbon House sometimes offers a walk-up window on Bourbon Street serving Parisian crepes, savory or sweet, and a selection of gelato along with beer and the frozen milk punch cocktail “to go.”

Outside the French Quarter, 2004 saw the introduction of two new fine dining restaurants from members of the Brennan family, each serving fresh interpretations of Creole cuisine in unique and distinctive settings. In the Central Business District, the same branch of the family that runs Commander’s Palace opened Café Adelaide (300 Poydras St., 504-595-3305) in the Loews Hotel, and named for an eccentric relative of the founders. In Mid-City, adjacent to the beautiful gates of City Park, Ralph Brennan opened Ralph’s on the Park (900 City Park Ave., 504-488-1000) in an extensively renovated 1860-era building with many windows taking full advantage of the lush views of live oaks and Spanish moss across the street.

Ian McNulty is a freelance food writer and columnist, a frequent commentator on the New Orleans entertainment talk show “Steppin’ Out” and editor of the guidebook “Hungry? Thirsty? New Orleans.”

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Young Guns and Veteran Masters: Catching Up with the Best Local Jazz Players

Kids grow up in New Orleans with dreams of being jazz musicians rather than rock stars. The trumpet is regarded locally as a sexier instrument and members of high school marching bands have the incomparable locker room bragging rights of accompanying Mardi Gras parades through the city streets during Carnival. Many of these kids do grow up to become successful jazz performers, helping to refresh the local scene and bring the sounds of New Orleans to audiences worldwide.

Here are some of the best-known and respected jazz musicians performing in New Orleans today – from the influential masters to some young up-and-comers – along with suggestions on where to catch them around town:

Top to Bottom: Kermit Ruffins; Irvin Mayfield

Kermit Ruffins

Kermit Ruffins, the consummate entertainer, seems to embody the spirit of the city – laid back, swinging and joyous all at once. The trumpeter and bandleader’s sets feature classics from his idol, Louis Armstrong, and his own free-spirited, be-bopping original material. On stage, Ruffins could be decked out in a suit or a T-shirt but always has a fedora on his head and a smile on his face. He was a founder of the Rebirth Brass Band, an ever-changing amalgamation of young musicians who since the 1980s have helped revive the city’s vital street music and introduce it to a worldwide audience. Ruffins plays with his band, the Barbecue Swingers, all over town, often playing several gigs in a day. His Thursday night set at Vaughn’s Lounge (4229 Dauphine St., 504-947-5562), a corner barroom deep in the Bywater neighborhood, has been a stop on the city’s music circuit for years.

Top to Bottom: Terrence Blanchard; Tim Laughlin

Irvin Mayfield

Irvin Mayfield, a prolific and innovative trumpeter , helped usher in a new direction for New Orleans jazz well before his 30th birthday through his close collaboration with drummer Bill Summers, the veteran percussionist from Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters. During late-night jam sessions at Summers’ home in the late 1990s, they launched Los Hombres Calientes, a band that takes the sounds of Cuba, Brazil and other Latin American traditions and reinterprets it through the prism of New Orleans jazz. Mayfield, who was in 2003 appointed to the post of cultural ambassador for the City of New Orleans, tours extensively with Los Hombres Calientes as well as performing other original material with his own sextet.

Terrence Blanchard

Terrence Blanchard, a Grammy Award-winning performer and composer, has a distinctive style of restrained, precise modern jazz that mesmerizes concert hall audiences and has been used as scores for Hollywood movies, particularly films by director Spike Lee. A New Orleans native son and graduate of the acclaimed New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, Blanchard gained national fame in the New York jazz scene and now tours internationally.

Tim Laughlin

Tim Laughlin’s style takes traditional Dixieland clarinet and introduces it to its relatives from the late 20th century and its future in the 21st. Original material from his latest album, the Isle of Orleans, drip with the local color and humor of modern New Orleans. Witness tunes like “Gentilly Strut,” “Dumaine Street Breakdown” and “Crescent City Moon,” which were all drawn from Laughlin’s experiences living and performing in the city. Though he’s said to be an heir to the mantle of New Orleans clarinet legend Pete Fountain, Laughlin’s performances are as unique as the city that inspires them. He performs most Mondays at the Jazz Parlor at Storyville District (125 Bourbon St., 504-410-1000).

Top to Bottom: Ellis Marsalis; Lionel Ferbos

Ellis Marsalis

Ellis Marsalis, regarded as the city’s most influential modern jazz pianist, gives audiences an earful with sets of hard bop, jazz standards and ballads and traditional New Orleans tunes. During a long career that began with a music assignment in the military, Marsalis has been a jazz educator as well as performer, holding several prestigious music chairs at high school and college levels. He is the father of six, including the musicians Branford, Jason, Delfayo and Wynton Marsalis, who is now artistic director of Jazz at New York’s Lincoln Center. When he isn’t touring, Marsalis holds court most weekends at Snug Harbor (626 Frenchmen St., 504-949-0696), the city’s premier contemporary jazz venue located just outside the French Quarter. His son Jason frequently joins him on drums for these shows.

Lionel Ferbos

Lionel Ferbos was afflicted by asthma as a child and told he couldn’t play the horn. Ignoring this discouragement, he bought his first cornet at a Rampart Street pawn shop and began a musical career spanning the better part of the 20th century and continues into the current millennium. Now in his nineties, Ferbos still delivers old time New Orleans jazz favorites as the leader of the Palm Court Jazz Band, which plays Saturday nights at the Palm Court Jazz Cafe (1204 Decatur St., 504-525-0200).

Top to Bottom: Trombone Shorty; Jeremy Davenport

Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews

Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews, is tall, lanky and evidently still growing, but the teenager’s memorable moniker has nonetheless stuck. The nickname was first applied when, at age five, he was spotted at a second line parade lugging a trombone longer than he was tall, blowing it loudly if not melodically. The scion of a prolific New Orleans music family that includes trumpeter James Andrews, the self-styled “Satchmo of the Ghetto,” Trombone Shorty spent his childhood performing with the city’s great players in clubs, at parades and even at Jazz Fest. His traditional musical style is shot through with youthful energy. He can be found joining the Monday jazz jam at Donna’s Bar and Grill (800 N. Rampart St., 504-596-6914) and at solo gigs at Blue Nile (532 Frenchmen St., 504-948-2583)

Jeremy Davenport

Jazz singer and trumpeter Jeremy Davenport performs with his band in the posh setting of the On Trois Lounge (which becomes the Jeremy Davenport Lounge on Thursdays) at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel (921 Canal St., 504-524-1331). The famous hotel chain spent some $250 million to transform a former department store into a luxury destination, and not a dime of that sum appears missing in the opulent bar, all soft lit and trimmed in thick molding and dark, polished woods. Davenport completed world tours with Harry Connick Jr.’s Big Band, and his own smooth, debonair style is often favorably compared with that of Chet Baker. During his performances Thursdays through Saturdays, The Lounge pushes back its tables from the front of the stage to open up dance floor space. Around the room, couples who could be on first dates or celebrating 50th anniversaries listen, watch, dine and drink from candle-lit tables.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Crossing Esplanade: French Quarter’s Neighbor Is a Bustling Bohemian Scene

Top to Bottom: Holy Smokes Cafe, Hand-rolled cigars from New Orleans Cigar Factory, Cigar Rolling Demonstration at Cigar Factory, Dickie Brennan’s Steakhouse.

Cigars may not be native to Louisiana, but they have certainly taken firm root in the city’s celebrated culture of indulgence.

The traditional finale to a rich meal, the cigar is also used to mark an important event such as the birth of a child or the completion of a big business deal. It’s no surprise then that a city that loves its fine cuisine and is willing to launch into boisterous celebration on the smallest pretext should prove a welcoming home for the cigar.

On A Roll

A fine cigar, after all, is to a common smoke as a bowl of dark, rich gumbo is to a can of soup: incomparably finer and more lavish. It’s also a handcrafted product made by artisans, rather than a mass-produced commodity, as one visit to the New Orleans Cigar Factory (415 Decatur St., 504-568-1003) will demonstrate vividly. In a bustling atmosphere fueled by meringue music and the ever-present aroma of just-lit cigars, a team of cigar makers works rapidly and with focus at a line of rustic wooden booths, rolling the establishment’s proprietary blends as visitors look on. Turning a pile of tobacco into a properly formed, appropriately aged and carefully maintained cigar is a long process, and each step is on display here, from the rolling table to the aging room to the walk-in humidor. The Cigar Factory operates a second location closer to the all-night action on Bourbon Street (206 Bourbon St., 504-568-0168), which is open much later.

While these cigars are New Orleans originals, many aficionados have brand loyalty and are only willing to stray from their favorites for so long. The French Quarter has several tobacconists offering large selections from well-known cigar makers, as well as specialty cigarettes and pipe tobacco. For example, the Crescent City Cigar Shop (730 Orleans Ave., 504-522-4427) and JAI Bawani (729 St. Louis St., 504-586-0994) both look and function much like the cigar shops visitors are likely familiar with from home. Much more exotic, however, is the retail experience at Rev. Zombie’s House of Voodoo (723 St. Peter St., 504-486-6366), where altars of religious statuary, ritual totems, candles and other curios share shop space with a wide selection of cigars and other tobacco products.

Where There’s Smoke, There’s Dinner

At Broussard’s Restaurant (819 Conti St., 504-581-3866), one of the “grande dames” of Creole dining, cigars are part of what the restaurant calls the “Three Fine C’s.” Fine cigars, fine cognac and fine coffee form a veritable holy trinity of after-dinner luxury at the 84-year-old Creole restaurant, which stocks Davidoff cigars, a highly-regarded brand from Switzerland.

Cigars are paid similar respect at Dickie Brennan’s Steakhouse (716 Iberville St., 504-522-2267), an upscale steakhouse where the aroma of a cigar rounds out a distinctly gentlemanly atmosphere of polished wood interiors and a no nonsense menu of USDA prime steaks and New Orleans seafood favorites. The steakhouse offers a selection of cigars from the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Honduras and Jamaica. Cigar smoking is allowed in the bar, and upon request in private dining rooms.

Holy Smokes Cafe (533 St. Louis St., 504-588-1811) truly lives up to its billing as a smoker’s cafe. In addition to a walk-in humidor, the cafe has a gourmet coffee bar as well as a selection of gelato, the luxuriously rich and creamy Italian ice cream. Try a cup of the coffee gelato for a mellow and flavorful icy treat. Big comfortable rocking chairs and a selection of magazines invite lingering over a freshly-lit stogie.

Most of the cigar shops also sell smoking accessories, from utilitarian cigar cutters to beautiful humidors. But a stop in to M.S. Rau Antiques (630 Royal St., 504-523-5660), gives a unique historical perspective to just how seriously the cigar culture was regarded in the gilded age and earlier. This immense antique mecca boasts a collection of cigar smoking accessories, including some crafted by renowned makers such as Tiffany, Faberge and Cartier.

Often made from gold and sterling and sometimes even encrusted with gemstones, these antiques can command kingly sums. For much less treasure, however, visitors might well feel like kings and queens themselves with a fine cigar in hand strolling under the balconies and Creole moon of a French Quarter evening.

Ian McNulty is a freelance food writer and columnist, a frequent commentator on the New Orleans entertainment talk show “Steppin’ Out” and editor of the guidebook “Hungry? Thirsty? New Orleans.”

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Marsalis Masters: New Orleans’ First Family of Jazz

When the University of New Orleans wanted to hold a concert in 2001 to mark the retirement of the school’s jazz studies director, organizers had to recruit just one bass player to round out their ensemble for the show. They knew all the rest of the players they needed – the trumpeter, the trombonist, the drummer and the saxophonist – would be at the retirement party regardless. Of course, that’s because the honoree was their father – Ellis Marsalis, the modern jazz master and patriarch of what has been called “the first family of jazz.”

That this retirement party concert would be recorded, packaged and distributed as a major musical release is no surprise given the stature the members of the Marsalis family performing on it hold in the jazz world. “The first family of jazz” is quite a title to live up to, though this clan does so in several distinct but related ways.

Firstly, they are a family of talented musicians. Ellis the father is a pianist, and four of his six sons – Branford, Wynton, Delfeayo and Jason – each took up the mantle (his sons Ellis III and Miboya chose other careers). As musicians, they are prolific, with enough recordings bearing the Marsalis name to constitute its own collection. But the family’s full impact comes not just from their commercial successes but from the various roles they have held in the development of modern American jazz, both in terms of innovation and education.

Ellis

Ellis had his first gig in 1949 playing tenor sax for a local New Orleans band called the Groovy Boys, but soon devoted himself to serious study of the piano. He joined the Marine Corps and was assigned to the service’s band, which gave weekly TV performances in the mid-1950s. Returning to New Orleans, he gigged around town, playing with Bourbon Street jazz legend Al Hirt among many others. By the 1970s, however, he began a career in music education that would become a cornerstone of his legacy in music. From his post at the public school system’s New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts, he taught countless young people including many who would go on to great musical acclaim, including Grammy Award-winner Harry Connick Jr. and Grammy Award-nominee Terence Blanchard. Through the 1990s, he led the jazz studies program at the University of New Orleans.

Of all the musicians who learned at his side, however, Ellis’ sons proved the most apt pupils. His two eldest sons, Branford and Wynton, each burst onto the music scene in the early 1980s, first joining jazz master Art Blakey for a tour of Europe with his ensemble the Jazz Messengers. Solo recordings quickly followed for Branford the saxophonist and Wynton the trumpeter as did international attention.

Wynton

Wynton left New Orleans for New York, where he has since built a musical career that has made him both a world-renowned performer and recording artist as well as a leader in promoting the art form to new audiences. In addition to contemporary jazz, Wynton has maintained a highly successful classical music career including concert, chamber and solo music for trumpet. In 1983, he won Grammy Awards in both classical and jazz, making him the first recording artist to win in both categories simultaneously. He has since netted a total of eight Grammy Awards for his jazz and classical recordings. In 1997 he won the Pulitzer Prize in music for his composition Blood On the Fields, a musical work about slavery.

In 1987, he co-founded Jazz at Lincoln Center, the world’s most prominent jazz institution where he serves as director today. Jazz education has been a centerpiece of Wynton’s work with the New York organization, with highly successful programs such as his Jazz for Young People series. This program in turn spawned his award-winning National Public Radio series Marsalis on Music. While touring, Wynton and his bands regularly conduct classes at local schools, using the star power of his name to engage young audiences.

Though he lives in New York, Wynton is still very much involved with the cultural life of his native New Orleans. Soon after Hurricane Katrina struck, Wynton was named to the mayor’s Bring New Orleans Back Commission cultural committee and he frequently appeared in national media as a commentator and advocate for the city’s cultural traditions after the storm. He had long been working in collaboration with the Ghanaian master drummer Yacub Addy on a composition called Congo Square. This 80-minute, 14-piece work drawing on the history and spirituality of Congo Square, a modern day park where in antebellum days slaves were allowed to congregate, play drums and dance. Wynton debuted the piece in the same park on a sultry afternoon during the 2006 French Quarter Festival, an especially celebratory event for the community in the year after Hurricane Katrina.

Branford

The diversity of Branford’s musical projects seems as boundless as Wynton’s, bringing his influence to a wide range of areas. From contemporary jazz, Branford has also taken on classical material, recording and performing with chamber orchestras. In 1991, his work on the music for Spike Lee’s film “Mo’ Better Blues” resulted in a merging of jazz and rap. A year later, he found himself on national TV every night as musical director for the Tonight Show. In 1994, his direction took an avant garde bend with the formation of Buckshot LeFonque, a project blending rock, R&B, hip-hop and blues with a jazz sensibility with a dash of spoken word poetry courtesy of Maya Angelou.

Following in his father’s footsteps as a jazz educator, Branford has been artist in residence at several major American universities, and brings his Marsalis Jams educational music series to other campuses around the country. A Grammy-award winner, Branford began the recording label Marsalis Music, which produces his own music and that of promising young performers.

Delfeayo

Delfeayo picked up the trombone, and by age 17 cut his first recording with his father. He has since been part of more than 70 major-label recordings, working with his brothers Branford and Wynton and many other top names in jazz. Four of his productions have won Grammy awards. Delfeayo has been the featured trombone soloist with such heavy hitters as Ray Charles and Fats Domino.

Like his brothers, Delfeayo’s work has tackled often difficult subjects and taken him far outside the realm of jazz standards and the classical canon. For instance, his original composition Pontius Pilate’s Decision is a 70-minute meditation on the pivotal biblical figure.

Jason

The youngest of the musical Marsalis brothers, Jason became the family’s drummer boy at the tender age of three when he started playing on toy drums. At age 14, he made his first appearance on the recording Heart of Gold with his father and played on two more Ellis Marsalis releases in the next few years. One of Jason’s most well-received projects was Los Hombres Calientes, a cross-cultural group he co-founded with New Orleans trumpeter Irvin Mayfield and legendary percussionist Bill Summers. The group combined Latin, Afro-Cuban, African and other styles with modern jazz, creating a hot sound that proved very popular in New Orleans and elsewhere. Jason left the band to pursue his solo career. He is now working with his father and his mother Dolores on a new recording label, to be called Elm Records.

Apart from scoring an invitation to the next Marsalis family celebration, the best place for visitors to New Orleans to catch a Marsalis performance is at Snug Harbor (626 Frenchmen St., 504-949-0696), the city’s premier contemporary jazz venue. Ellis performs there regularly, often with Jason on drums.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Edible Homework: Cooking Schools Share the New Orleans Culinary Experience

Visitors who think a clutch of plastic beads, a hurricane glass and an obscene T-shirt are the best they can bring back home from a trip to New Orleans clearly haven’t experienced one of the city’s distinctive cooking schools.

Anne Gormly has, and after a lunchtime class at the New Orleans School of Cooking (524 St. Louis St., 504-525-2665), the Georgia College and State University vice president was able to whip up a menu of Cajun dishes for a charity event when she returned home.

“We couldn’t find crawfish back home, but everything came out great anyway,” she says. “Everyone is still talking about that meal here.”

The Crescent City’s rich culinary culture is an essential part of the travel experience for many New Orleans visitors, and cooking schools in the French Quarter and elsewhere offer a unique way to tap in to that culture. If going to school isn’t quite your idea of a vacation activity, don’t be put off. These programs offer “students” a fun, interactive curriculum covering a few recipes in about the time it takes to watch a movie. The best part: participants get to dine on the multi-course meal they have just learned how to prepare.

Frank Leo, general manager of the New Orleans School of Cooking, says guests appreciate the value of a cooking class, which at his operation includes instruction, take-home recipes and a three- or four-course meal for $20 to $25. The school has been around for 25 years and holds three-hour or two-hour classes daily in a renovated 1830’s -era molasses warehouse, as well as hosting private classes for groups of 25 or more.

Returning visitors sometimes book a reservation months in advance, Leo says, while a rain squall or an especially hot day in the French Quarter will generate more spur- of-the-moment visitors looking for an interesting indoor activity.

Cooking Around Town

The continuing culinary culture of New Orleans relies as much on the skill and creativity of its chefs and food entrepreneurs as it does on the canon of Creole cookery, and those chefs and promoters are hardly hemmed in by tradition. In fact, a growing cadre of cooking schools and gourmet experiences are flourishing in the city post-Katrina and offering visitors and local foodies many delicious opportunities to expand their culinary horizons. Here are a few notable players operating not far from the French Quarter:

In the House on Bayou Road just outside the French Quarter, The New Orleans Cooking Experience (2285 Bayou Road, 504-945-9104)offers half-day classes, series classes and luxury cooking school vacations featuring traditional Creole recipes and menus taught by noted New Orleans chefs like Frank Brigsten and Gerard Maras.

Cookin’ Cajun Cooking School began as a praline stand in Jackson Square before evolving into a large theater-style cooking school and restaurant in the Riverwalk Mall (1 Poydras St., 504-586-8832) offering classes on weekends and by appointment. A view of the Mississippi River as well as the chef instructors is an added bonus here.

Savvy Gourmet hosts its classes, restaurant, catering kitchens and retail store in a trendy space on the Magazine Street corridor uptown (4519 Magazine, 504-895-2665) Local foodies have flocked to the classes and events promoted in Savvy Gourmet’s breezy irreverent style.

Culinaria (1519 Carondelet St., 504-561-8284) offers classes, demonstrations and culinary explorations in food, wine and spirits in a handsome restored mansion one block off St. Charles Avenue.

Ian McNulty is a freelance food writer and columnist, a frequent commentator on the New Orleans entertainment talk show “Steppin’ Out” and editor of the guidebook “Hungry? Thirsty? New Orleans.”