The Ultimate Guide for Women Traveling Solo in the French Quarter

Photo by Court Prather on Unsplash

If you are a woman who likes to travel solo, New Orleans is well-suited for experiencing on your own. Whether you’re traveling for leisure or work, there’s much to explore, and the well-honed tourism industry ensures that you feel welcome, safe and comfortable, and that your needs are met. It’s not just about catering to visitors, however. People here are friendly and warm in general, from the service industry folks to locals to fellow travelers. The place just has that effect on you.

This means that, for one, eating alone is not a problem. You can eat at the bar counter in lots of restaurants, which offer from bar snacks and small-plate happy hour specials to full meals (many have oyster bars as well). And you’ll probably be making friends everywhere you go. That said, we have our own recommendations for where to stay, eat and play, so read on to learn how to make the best of your solo trip to New Orleans.

A Note on Safety

When traveling alone, safety is one of the top concerns for women, not just in New Orleans, but everywhere. The best way to stay safe while you’re enjoying New Orleans is to use your common sense — just as you would anywhere else:

- Don’t walk alone in quiet and dark places. Stick to bright, populated areas with foot traffic. The French Quarter in particular is an enchanting place, and it’s tempting to explore its nooks and alleyways, but do it only when there are other people around.

- Consider exploring in ways that would allow you to be surrounded by people, such as attending a festival or a live music concert, or booking a tour.

- Don’t venture out at odd times of day or night alone, when the streets are likely to be deserted.

- Guard your belongings when you’re out.

- Leave your valuables in the hotel room (in a locked safe, if possible).

- Do make new friends, but trust your instincts and be careful not to trust strangers too quickly.

- Make sure your friends and/or family know where you are, and check in often.

- Don’t try to save on services and amenities that can compromise your safety, and opt for a hotel in a safer neighborhood, or take a cab instead of walking.

- New Orleans is a party destination with a strong drinking culture, and the French Quarter is packed with bars, not to mention you can drink on the street as long as it’s from a plastic container. Drinking excessively can leave anyone vulnerable, so watching your alcohol intake, being aware of your surroundings, and taking a cab or a rideshare back to your hotel instead of walking would add extra levels of protection when you’re out enjoying yourself. You can also join a culinary or a cocktail tour — that way, you can still eat and drink your way through the French Quarter, but you’ll be guided and with other people at all times.

Where to Stay

The safest and most practical way to enjoy the French Quarter to the fullest is to stay in one of the hotels located in the French Quarter or nearby. Most places of interest will be within walking distance, and the streets will be filled with people at all times of day and night. We recommend French Market Inn, Hotel St. Marie, Place D’Armes, and Prince Conti Hotel.

Not only are they charming but they’re all located within walking distance of many sights, bars and restaurants. French Market Inn, Place d’Armes Hotel and Hotel St. Marie all have saltwater pools tucked away in serene tropical courtyards, which are perfect for both lounging with a cocktail and working remotely undisturbed.

Where to Eat and Drink

Solo women travelers needn’t worry about dining alone in the French Quarter. Most businesses are used to travelers, alone or in groups of any size, and many restaurants also have roomy bars where you can get everything from a full meal to bar snacks (this includes sushi and oyster bars).

Some French Quarter restaurants are particularly well-suited for dining alone, including the vegetarian-friendly and cozy Bennachin or the charming, dimly lit Sylvain. For some old-world elegance in a relaxed setting head to Muriel’s Jackson Square, Tujague’s, or the Hermes Bar at Antoine’s. All three are great options for Creole cuisine and classic cocktails (and Tujague’s prix fixe menu is an excellent way to sample some staples).

The Red Fish Grill and Bourbon House of the Brennan family both have popular happy hours and long, comfy bars. Or grab a seat at the bar at Mr. B’s Bistro, which is popular among the business lunch crowd and the spot to try BBQ shrimp (do wear that bib).

If you find yourself hankering for a burger late at night, the front bar at Buffa’s (across the street from the Quarter on Esplanade Avenue) is open till 2 a.m. every night, and the place is always teeming with both locals and visitors alike and has nightly live music. And, for solo dining with a view, try Tableau, which opens up onto Jackson Square, or, for more casual fare, see if you can score a balcony seat at Crescent City Brewhouse. Finally, one of the best spots for people-watching is the lively sidewalk seating at Palace Cafe, located on a busy stretch of Canal Street.

Where to Work Out/Outdoor Activities

There are plenty of safe, comfortable places to stay fit if you’re a woman traveling solo in New Orleans. Your best bets in the French Quarter are below.

“For residents and travelers at all levels of practice,” Yoga at the Cabildo classes are held at the historic Cabildo on Jackson Square. History meets fitness in a sun-filled gallery inside a 1700s Spanish colonial building, which also houses an excellent museum. For all fitness levels.

Exercise surrounded by opulence at the New Orleans Athletic Club on N. Rampart Street on the edge of the Quarter. Established in 1872, the club has seen quite a few famous people, from Tennessee Williams and Huey Long to the contemporary Hollywood celebrities who film here. As one of the oldest athletic clubs in America, NOAC boasts a pool, sauna and steam room, a well-stocked library, spa, coffee stations, and even a bar.

Speaking of parks, there are three large outdoor public spaces in and near the French Quarter, excellent for walking and biking. Crescent Park connects Faubourg Marigny — located at the edge of the Quarter — to the Bywater neighborhood, all via a long, waterfront park that hugs the contours of the Mississippi.

Woldenberg Riverfront Park is the easiest means of accessing the Mississippi Riverfront for people-watching, admiring the ships going by, or a quiet walk along the river. And, right across N. Rampart St. where the Quarter meets Tremé, is the 32-acre Armstrong Park, the site of many festivals and the legendary Congo Square, and a great spot to watch the birds and the turtles.

Getting Around

There are so many ways to explore the Quarter — on foot or bike; aboard a big red double-decker bus, mule-drawn carriage, or rickshaw. If you’re looking for a self-guided adventure, many local companies will let you rent a bike for several hours and up to several days, and most of the time helmet, bike lock, maps, and “concierge support” are included in the rental fee. Though slowly, New Orleans is getting more bike-friendly with the recently repaved roads, new dedicated and shared bike lanes, and increased bike safety awareness. And, hey, no hills!

Taking a Tour

There are lots of tours you can take without leaving the French Quarter. The ones you should choose depend on your interests and the preferred means of transportation. The history of the French Quarter in particular is teeming with ghost stories, so what better way to learn about the city’s often turbulent and sordid past than taking a ghost tour? You can also take a culinary or cocktail tour, or a combination of both. And, if you want to get off land for a few hours, there’s no better way to see the mighty Mississippi than a cruise on the Creole Queen.

Visiting a Museum

Stay cool indoors and learn about local history at the same time at one of the numerous French Quarter museums, all within walking distance from one another. We especially recommend the New Orleans Jazz Museum and the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum, housed in the former 19th-century apothecary shop and filled with cool surgical instruments and patent medicines.

Both The Cabildo and The Presbytère, which flank the St. Louis Cathedral, are run by the Louisiana State Museum. The Cabildo houses such precious artifacts as a painting of Marie Laveau by Frank Schneider and a rare Napoleon’s death mask.

A former courthouse, The Presbytère contains two permanent exhibits, among several others. The dazzling “Mardi Gras: It’s Carnival Time in Louisiana” tells the story of Carnival traditions in Louisiana, including Cajun Courir de Mardi Gras, Zulu coconut throws, Rex ball costumes, and much more. The “Living with Hurricanes: Katrina and Beyond” exhibit documents the natural disaster and the ongoing recovery.

Shopping

French Quarter is full of both national chains like H&M and Sephora, and quirky one-of-a-kind stores. From hats to locally made art to souvenirs, we got you covered.

Within walking distance of the French Quarter, the Canal Place mall houses Saks Fifth Avenue, Anthropologie, Michael Kors, and many more upscale retailers. For locally made goods, check out the daily flea market at the French Market and Dutch Alley Artist’s Co-Op.

United Apparel Liquidators (UAL) is unsurpassed for hunting name brands with deep discounts. Also on Chartres Street, Hemline is a popular boutique that carries a well-curated shoe and women’s fashion collection from local and national brands. Located next door, the Red Lantern offers a unique, funky selection of clothing.

You’ll find retro-inspired clothing, corsets, lingerie, and accessories at Trashy Diva. A funky retro-inspired boutique not unlike Trashy Diva, Dollz & Dames sells vintage-inspired clothing, shoes and accessories. (You can’t miss its eye candy of a storefront on an otherwise sleepy side of the block.) The same goes for Lost and Found, if you’re looking for some fun retro/pinup scores.

Since we’re a costuming city, we highly recommend Fifi Mahony’s. They’ll help you find a perfect wig, and makeup and accessories to go with it. If you’re looking for locally made jewelry with some NOLA-centric designs, check out Porter Lyons.

For a taste of esoteric New Orleans, the quiet Voodoo Authentica is well worth a visit for its handmade dolls, gris-gris bags, candles, oils, and Haitian and African spiritual arts and crafts, including the remarkable Haitian vodou drapeau (flags). The in-house practitioners also offer spiritual readings and consultations.

We hope you enjoy your stay in the French Quarter, and happy travels!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Must-See French Quarter Courtyards

Photo courtesy of Hotel St. Marie

There’s no shortage of grand courtyards in the Quarter. Many of these are, obviously, located on private property, but some are open to the public. Le Monde Creole walking tour is an excellent introduction to New Orleans buildings, including some of the Quarter’s loveliest courtyards.

The following fantastic examples of indigenous New Orleans design should not be missed by travelers, especially those who are interested in art and architecture.

Beauregard-Keyes House

1113 Chartres Street

One of the most well-known historic homes in the Quarter, this 1826 Center Hall classic of the genre actually boasts two outdoor spaces, although only one is a proper French Quarter courtyard. The first space is a garden which is a popular wedding destination. Ensconced by brick walls (but visible from the street if you can boost yourself and peak over the top), the garden is surrounded by low hedges and brick pathways. In the back of the house, a more spacious courtyard is simply a lovely setting for many a special New Orleans event or celebration. The house can be visited on a formal tour.

Cane & Table

1113 Decatur Street

The backyard at this cocktail bar is a Quarter courtyard that pretty much screams “tropical indulgence.” To be fair, that characterization is aided and abetted by the Cane & Table menu, which includes a long list of tropical drinks that eschew sugar overload and instead present a slate of complex fruit concoctions. Order something with rum in it and find a spot to chill under the palms and on the pretty tiles that make up this wonderful hidden gem of New Orleans’ outdoor architecture.

French Market Inn

509 Decatur Street

Located about a 10-minute walk from the marketplace that gives this hotel its name, the French Market Inn’s courtyard is interesting, in that it gives off more of a brick-and-mortar sense of stately presence as opposed to a leafy green secret garden. It’s still an oasis from the street scene of the French Quarter — the muscular stone walls buttress the isolation that guests have from the noise outside, enhanced by the presence of a teal-blue pool.

Hermann-Grima House

820 St. Louis Street

The Hermann-Grima House is one of the most popular historic homes open to visitors to the French Quarter. At times a home for some of the city’s most prominent merchant families, today the House offers tours that provide insight into both the history and architecture of New Orleans and the French Quarter. The spacious courtyard is one of the most beautiful features of this historical home and has been the backdrop of many a New Orleans wedding.

Hotel St. Marie

827 Toulouse Street

Head just off Bourbon Street to find Hotel St. Marie, which encompasses an exemplary tropical courtyard that is romantic as all get out on sultry New Orleans evenings. Wrought-iron accents, a sunset-esque color scheme, and swaying palm fronds set off a courtyard pool that feels simultaneously adjacent to and removed from the busy Quarter dining and nightlife, which is a stone’s throw away. Guests can enjoy the setting from outdoor balconies that look down upon the pool and the surrounding courtyard space.

Pat O’Brien’s

718 St. Peter Street

Most visitors to New Orleans have at least heard about the (in)famous Pat O’Briens Hurricane, but this iconic bar doesn’t just sling neon-hued cocktails. It’s also anchored by a gorgeous courtyard that is widely regarded as one of the most attractive in the Quarter. The central fountain has been the photographic background of many a happy New Orleans memory. To be fair, Pat O’Brien’s gets pretty lively, so you may not be focused on the outdoor architecture, but try and take a moment to appreciate the space before you order that next Hurricane.

Place d’Armes Hotel

625 St. Ann Street

Head just off of Jackson Square, between Royal and Chartres streets, to find the Place d’Armes and its classic courtyard. The space is offset by brick walls and shade trees that catch the breeze, which is a nice spot to be in as you sit by the pool and enjoy life. Guests can look out onto the courtyard from the rows of outdoor balconies — a historical accent that allowed the occupants of these buildings to soak up the fresh air and cool breezes even in the midst of a New Orleans summer.

Prince Conti Hotel

830 Conti Street

Located between Bourbon and Dauphine Street, and across the way from iconic New Orleans restaurants like Arnaud’s and bars like French 75 and the Erin Rose, Prince Conti is a historic gem within the city’s hotel pantheon. The courtyard is lush and green, set off by classical statuary that adds to the old-school atmosphere. You can dine on Creole cuisine in the Cafe Conti, or enjoy a good drink in rarefied air in the impeccable Bombay Club.

The Court of Two Sisters

613 Royal Street

This courtyard is so great they named the restaurant after it. This is one of the more romantic dining destinations in the Quarter, swathed in leafy shade and elegant ambiance. Still, the Court doesn’t dine out, as it were, on its location alone — the Creole menu and the jazz brunch are staples of the local culinary scene. The location is steeped in history: In 1726, it was the original residence of Sieur Etienne de Perier, the second French governor of colonial Louisiana, and President Zachary Taylor once resided here.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

533 Royal Street

It should come as no surprise that one of the city’s top historical learning institutions is also the site of a courtyard that ranks among the Quarter’s best. This relatively thin courtyard connects many of the collection’s excellent exhibition halls, and is also the location for Concerts in the Courtyard, a concert series that regularly features some of the city’s best musicians.

If you’re planning a stay in New Orleans, be sure to check out our resource for French Quarter Hotels.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Micaela Almonester Pontalba: The Baroness of Extremes

Baroness Micaela Almonester Pontalba. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

Micaela Almonester Pontalba was the wealthiest woman in New Orleans, but her biographer called her a frump for her lamentable everyday wardrobe. Like most Creoles, she married a cousin, but her in-laws turned out to be more interested in her money than in family love and loyalty.

She grew up in New Orleans where she completed her greatest work, but spent most of her adult life in Paris. She is known to history as the “Baroness Pontalba,” a title inherited by a lackluster husband as she was about to divorce him.

Contemporaries called her persistent, bright-eyed, intelligent, vivacious, prompt, shrewd, and business-like. Male historians characterized the Baroness as strong-willed, imperious, penurious, self-indulgent, and vacillating, while her female biographer uncovered a life of affliction and resilience. Her portrait as a young wife shows a woman of grace and reflection; her photograph at an older age shows a hardened veteran with unmistakably masculine features.

Married to Misery

No contradiction was greater than the chasm between Micaela’s privileged life and her sufferings at the hand of her husband’s family. Born in 1795, she was married to her cousin Xavier Celestin de Pontalba at the age of 15. Her father, Andres Almonester y Rojas, had been a wealthy New Orleans notary and politician who amassed a fortune in colonial real estate with the indulgence of Spanish authorities.

In 1777, the crown allowed him to acquire public land on both sides of the town square, which he developed into a lucrative rental property and the base of a fortune. Micaela’s father-in-law was Baron Joseph Delfau de Pontalba, who served the French and Spanish as a military officer and lived in a state of paranoia about money and social control.

Almonester was 70 years old when Micaela was born, and died just three years later. In a marriage contract of 1811, her widowed mother agreed to an expensive dowry for her daughter to seal the alliance with their socially prominent Pontalba cousins. After her wedding, Micaela was promptly whisked from New Orleans to Mont l’Eveque, the Pontalba family chateau near Paris.

Micaela bore her husband five children, but the influence of his father on their marriage was disastrous. It soon became apparent that the elder de Pontalba was intent on seizing the Almonester fortune. Two years after the wedding, he had her sign a general power of attorney to her husband giving him control of her assets, rents, and capital, both dotal and as heir of her father.

French law provided a “head and master” marital regime, but husbands had grave obligations to account for their wives’ funds, mortgaging their own assets as a guarantee. Micaela began to suspect their intentions when she discovered that the elder Pontalba had no intention of fulfilling his side of the marriage contract and was appropriating her money.

No Way Out?

By the 1830s, Micaela was a virtual prisoner of the Pontalba family, who made her life miserable. If she visited New Orleans, she was accused of deserting her husband. In Paris, she began a series of lawsuits to get a separation but consistently lost to the strictures of the French law on marriage. Her efforts to protect her fortune enraged her father-in-law, who in November 1834 shot her point blank with a pair of dueling pistols at the family chateau. That evening, after brooding through the day, he took his own life with the same pistols.

With four round gunshots to the chest, fingers shattered, and blood pouring, Micaela survived. Several lawsuits later, she received her separation. In New Orleans, a civil law judge ordered the restitution of her property. She lived to build the elegant rowhouses known to history as the Pontalba Buildings, on Jackson Square, and a vast Parisian hotel, now used as the American Embassy. She died in 1874 at the age of 78.

Micaela’s life has been the subject of two books and an opera. Intimate Enemies, a riveting 1997 biography by Christina Vella, reads like a novel. Dense and vibrantly written, it portrays its subject sympathetically. Baroness Pontalba’s Buildings, an earlier and shorter work by the late architect Samuel Wilson, Jr. and historian Leonard Huber, shows respect for her accomplishments in building the Pontalba Buildings but lacks the pathos of the full story. Thea Musgrave’s opera Pontalba was commissioned as a fitting France-Louisiana subject to commemorate the Louisiana Purchase Bicentennial of 2003.

In the end, French law notwithstanding, the Baroness got her money back.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

French Quarter Guide to an Exciting New Orleans Bachelorette Party

You can hardly cross the street in the French Quarter these days without witnessing a merry krewe of bachelorettes spilling out of this bar or that restaurant. There are many good reasons for it, if you consider the whole months of perfectly mild weather, and all the opportunities to both relax and revel in one of the most splendid settings in the country, if not the world. New Orleans offers a backdrop both historical and modern — a perfect blend of ingredients to make your bachelorette party unforgettable.

Sky is the limit when it comes to eating, drinking and shopping in New Orleans, but you have to start somewhere. So here are some suggestions to help your bachelorette party have a great time in New Orleans.

Breakfast or brunch

Start the day off right with a hearty breakfast at Stanley. Not only will you have a view of Jackson Square, but you’ll have a choice of several very Louisiana eggs Benedict options (topped with seafood and Creole Hollandaise, or served as a po-boy).

Feeling more like brunch? Heading in another direction lies an award-winning brunch spot, the Ruby Slipper. This local mini-chain’s French Quarter location at 204 Decatur Street isn’t as crowded as the Mid-City one, but even if you have to wait a little for the table, the Ruby Slipper’s Eggs Cochon and BBQ shrimp and grits are well worth it. The signature items are also offered in lighter versions (Skinny Migas, Skinny Florentine). There’s another location nearby, in the Central Business District (CBD), at 200 Magazine Street.

Speaking of CBD, the Willa Jean bakery and cafe deserves the trek out of the French Quarter for its Southern-inspired take on the weekend brunch featuring avocado toast, pancakes, and signature cornbread. Check out the mouth-watering descriptions of the “biscuit situation” on the menu.

The Country Club in Bywater has a drag brunch on Saturdays and Sundays at 10 a.m. and 1 p.m. that’s popular with bachelorette parties. Reservations are recommended.

Photo by Gary J. Wood on Flickr

Shopping

Within walking distance of the French Quarter, Canal Place houses Saks Fifth Avenue, Anthropologie, Michael Kors, and many more upscale retailers. For locally made goods, check out the daily flea market at the French Market or the Dutch Alley Artist’s Co-Op.

United Apparel Liquidators (UAL) is unsurpassed for hunting name brands with deep discounts. Also on Chartres Street, Hemline is a popular boutique that carries a well-curated shoe and women’s fashion collection from local and national brands.

You’ll find retro-inspired clothing, corsets, lingerie, and accessories at Trashy Diva‘s French Quarter outpost (537 Royal Street). And, speaking of shoes, check out John Fluevog Shoes. Since we’re a costuming city, we highly recommend Fifi Mahony’s. They’ll help you find a perfect wig, and makeup and accessories to go with it.

For a taste of esoteric New Orleans, the quiet Voodoo Authentica is well worth a visit for its handmade dolls, gris-gris bags, candles, oils, and Haitian and African spiritual arts and crafts, including the remarkable Haitian vodou drapeau (flags). The in-house practitioners also offer spiritual readings and consultations.

Photo courtesy of Beachbum Berry’s Latitude 29 on Facebook

Happy hour

There’s a good chance you could stumble into a great bar on your own if you just start walking in any direction, but we won’t steer you wrong with these suggestions either.

First off, The Bombay Club is a must if you are a martini lover and want some live music. The menu is a fresh take on British cuisine, with a Cajun twist. Or, toast the bride-to-be with a classic New Orleans cocktail like Sazerac in the Carousel Bar & Lounge at Hotel Monteleone. It’s posh, and it revolves (that’s right).

If you want bubbles, Brennan’s Roost Bar happy hour has Champagne cocktails and discounts on bottles of Champagne, plus a lush courtyard with plenty of space to accommodate large groups.

If you dig rum, Beachbum Berry’s Latitude 29 Tiki cocktails are magical potions that are mostly classic but with inventive twists.

Finally, if you’re feeling adventurous and want some serious New Orleans flair, why not try absinthe in a historic bar? The hole-in-the-wall Pirates Alley Cafe, just off Jackson Square, and the Old Absinthe House on the corner of Bourbon and Bienville streets have both been quirky, solid constants in this city, and serve many a mean absinthe-based concoction.

Are you planning to come to New Orleans for a bachelorette party? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Photo Ideas for Your Next French Quarter Vacation

Photo by Cheryl Gerber for FrenchQuarter.com

New Orleans is hands down one of the most photogenic places in the world. Its wrought-iron balconies and lush tropical courtyards, not to mention the craziness of Bourbon Street or the magical riverboats on the Mississippi River, would enhance anyone’s Instagram. While there’s a lot to see, do, eat, and experience during your visit, don’t forget to document your journey. Here are the best places to snap and share in the French Quarter. Pics, or it didn’t happen, right?

The French Market

This historic market was founded in 1791 as a Native American trading post and has been operating continually since, making it the oldest public market in the country. Similar in structure to a traditional European market, this open-air mall covers roughly five blocks, from Cafe Du Monde on Decatur Street across from Jackson Square to the daily flea market at the end of Esplanade Avenue.

Many retail shops and restaurants surround it in every direction. The flea market area hosts dozens of local artisans, plus vendors from all over the world. There are plenty of souvenir trinkets, belts with big fleur-de-lis buckles, cheap sunglasses, and fake gator heads, but you can also find African prints, handcrafted art objects, local music CDs, and local crafts.

French Market also includes a small pedestrian plaza on Dumaine and St. Philip streets called the Dutch Alley. The food stands at the Farmers Market Pavilion offer a slew of spices, produce and local food that is uniquely New Orleans — from pralines to oysters to the beignet mix or the hot sauce you’d want to take home.

French Quarter Courtyards

There’s no shortage of grand courtyards in the Quarter. Many of these are located on private property, but some of the Quarter’s loveliest courtyards are open to the public. They’re breathtakingly beautiful and are just begging to be photographed, while you might want to sit down and have a quiet, reflective moment to yourself.

Just to name a few, try to check out the historic gems of Prince Conti Hotel or Hotel St. Marie (this one with the pool), or the enviable open space of the Beauregard-Keyes House (also a popular wedding destination). The Court of Two Sisters and Pat O’Brien’s also both have stunning, sprawling courtyards — if you want a Hurricane or gumbo with your history lesson.

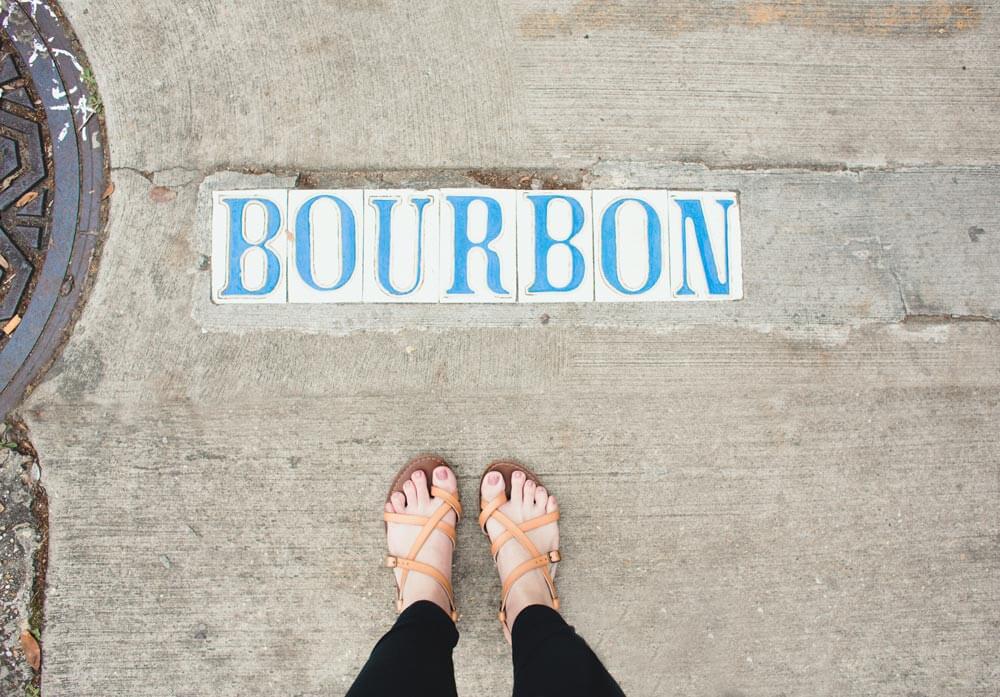

Jackson Square

Known since the 18th century as Place d’Armes, this timeless landmark was renamed in honor of Andrew Jackson following the 1815 Battle of New Orleans. Jackson’s bronze statue is the focal point of the square, surrounded by lavish flora and facing the Mississippi River. It’s perhaps one of the most recognizable images of New Orleans, along with the St. Louis Cathedral, the Cabildo, the Presbytère, and the Pontalba buildings flanking the square.

Jackson Square is also a host to the open-air artist market and performance space, with local art displayed along the fence. You can have your sketch done, dance to a brass band, or have your fortune told. Carriage rides are offered in front of the square. This bustling scene is great for experiencing and documenting!

JAX Brewery

Another unique and incredibly photogenic New Orleans landmark, JAX Brewery was once home to Jax Beer (from 1891 until the 1970s). These days this converted brewery holds a free museum devoted to brewing beer, as well as several floors of shops and restaurants. While you stroll through the beautifully renovated building, check out the view of the Mississippi River from the patio.

The Moonwalk Riverfront Park

You can access the mile-long Riverfront very easily from the Jackson Square area. There you will find the grassy Woldenberg Park and a walkway called the Moonwalk, named after the former New Orleans mayor Maurice “Moon” Landrieu. Woldenberg Park is a popular spot to watch the fireworks. It also hosts one of the largest stages during the annual French Quarter Festival, which takes place in the spring.

Stroll along the Moonwalk to view public art, like the Holocaust Memorial, and to watch the boats go by (look for classic riverboats like the Steamboat Natchez and the Creole Queen). The Riverwalk is also home to two popular family-friendly attractions, the Audubon Aquarium and the Insectarium.

Bourbon Street

That much is true: Bourbon Street is home to one of the wildest nightly street parties in the country. It’s well known for its karaoke and burlesque clubs, bars that never seem to close, and crowds milling about round the clock. It is also one of the oldest streets in the country, a vivid example of Spanish colonial architecture dating back to 1798 and steeped in history, magic, and legends. And it’s home to the city’s most iconic destinations like Galatoire’s and the Old Absinthe House (both with instantly recognizable facades).

French Quarter Balconies

The delicate, intricately woven ironwork is one of the most iconic features of New Orleans architecture. While you’ll find some stunning examples in the Garden District, the Quarter has the highest concentration of wrought iron within walking distance. You can spot it in the balconies, but also in the gates, fences, and even doors. Look for the decorative Victorian ironwork in the balconies all over the Quarter, but especially on Royal and Bourbon streets.

The French Quarter balconies are also the hotspots for the party scene, and not just during the Carnival. If you can snag an invite to a private party that takes place on the balcony, you’re lucky; otherwise, quite a few bars on Bourbon Street alone provide access to their people-watching party havens with incredible views and some bead-tossing opportunities.

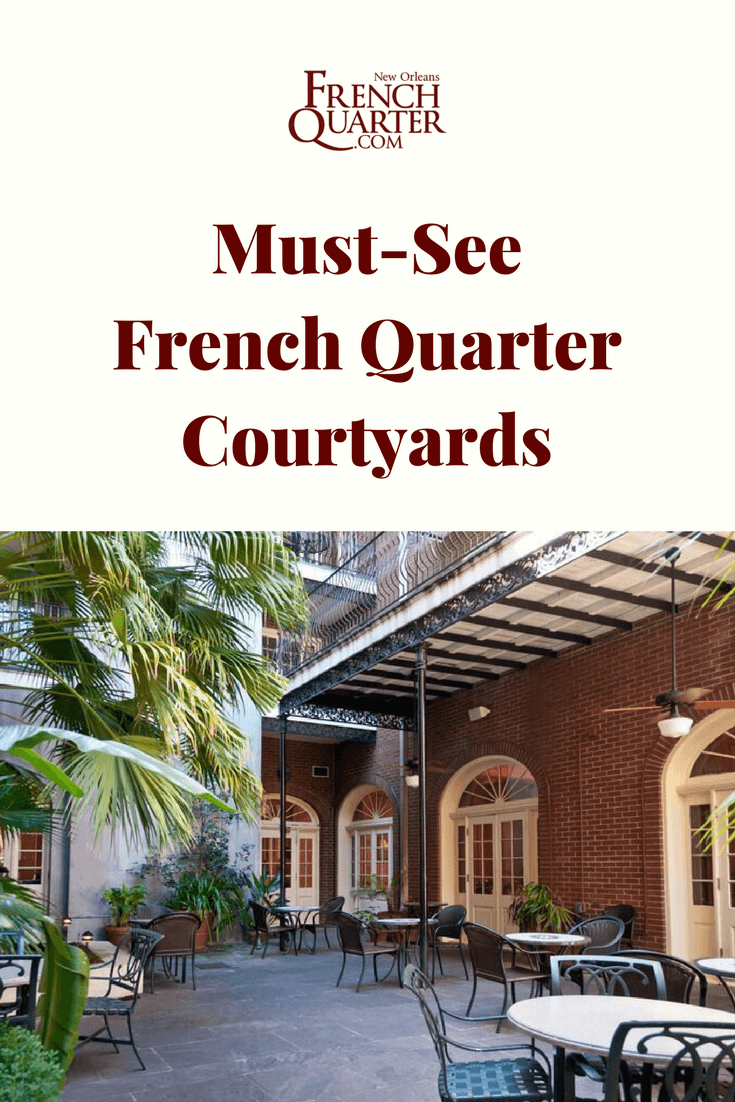

Under a Historic Street Sign

We’re talking about those colorfully tiled street signs embedded into the walls throughout the Quarter, one of the most vivid reminders that the French have ceded their colony in 1763 to the Spanish and that New Orleans remained under Spanish rule till 1803. When you’re wandering around the French Quarter look for the Calle signs in Spanish, 30 total. Some correspond to the streets’ existing names, like Bourbon and Toulouse, others bear the names that are no longer: Calle Real (Royal St.), Arsenal (Ursuline), Plaza de Armas (Jackson Square), Calle del Hospital (Governor Nicholls), Camino Real y Muelle (Decatur), and so on.

Eating Beignets

The bite-sized New Orleans staple, a beignet is one of those must-haves while you’re visiting, and what better place to try it than at Cafe Du Monde, a true New Orleans fixture by the French Market that closes only for Christmas and hurricanes? Not only your plate of beignets will be served piping hot and accompanied by a strong cup of café au lait, but once you sprinkle all that powdered sugar on your beignets (and, inevitably on yourself) it becomes Instagram gold.

Almost everyone coming to New Orleans has heard of Cafe du Monde, but Cafe Beignet (with three locations in the Quarter) seems to fly under a lot of radars. We especially recommend the Royal Street location, on a quiet, pretty block where the main company is begging pigeons and sparrows.

Street Tiles

The distinct blue-and-white street tiles that spell out street names at corners throughout New Orleans are unique to the city and date back to the 1870s. While it’s not entirely clear why the city leaders have opted to embed these ceramic tiles into the sidewalks, they are admired and often photographed. The locals feel strongly about their preservation, and at least two local companies create beautiful replicas for sale (Preservation Tiles and Derby Pottery). See how many tiles you can spot while you explore the Quarter!

Art Galleries and Antique Shops on Royal Street

The 13-block thoroughfare of Royal Street that runs parallel to Bourbon is one of the finest stretches of art galleries, antique stores, wrought-iron balconies, restaurants, and some of the best and the oldest architecture in the U.S. Among the notable art galleries are Harouni, featuring the artist’s own work; and George Rodrique Studios, with the late artist’s ubiquitous Blue Dog paintings on display.

As for shopping for antiques, from exquisite chandeliers to rare 17th-century furniture to fine art and rare jewelry, Royal Street also got you covered. M.S. Rau, for instance, is considered one of the best destinations in the world for antique shopping.

Happy photo-worthy exploring!

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Must-See Mardi Gras Museums

Photo courtesy of Mardi Gras World on Facebook

The magic of the Carnival is perpetually captured by these museums listed below, even outside of the season, which falls between January 6 (Twelfth Night, or Epiphany) and ends on Fat Tuesday, followed by the Lenten season starting on Ash Wednesday. Come admire the gowns and the tiaras, see how the floats are built, and learn just how much work goes into the fabulously beaded and feathered Mardi Gras Indian costumes. Trust us, you won’t find anything like this outside New Orleans.

Mardi Gras World

1380 Port of New Orleans Place

Mardi Gras World is located along the Mississippi River, next to the Morial Convention Center. More than 80 percent of the parade floats that you see on the streets of New Orleans during the Carnival season are designed and built at this 300,000-square-foot warehouse that belongs to Kern Studios. The history of Kern Studios dates back to 1947, when it was founded by float designer and builder Blaine Kern.

The guided tour covers the history of the Carnival that has begun in 1837 with floats pulled by mule-drawn carriages, including the balls, the krewes, and other traditions. If you want a tour, a Mardi Gras World shuttle can pick you up for free from one of the many designated locations downtown and in the French Quarter. There are no prearranged pickups, so just call 504-361-7821.

Also, feel free to take advantage of a free slice of King Cake offered at the end of the tour (it’s not easy to find out of season), and the great views of the Mississippi River from the on-site café.

The Presbytère

751 Chartres Street, Jackson Square

The Presbytère is located on Jackson Square, on the other side of St. Louis Cathedral. Known since the 18th century as Place d’Armes, this timeless landmark was renamed in honor of Andrew Jackson following the 1815 Battle of New Orleans. Jackson’s bronze statue is the focal point of the square, surrounded by lavish flora and facing the Mississippi River.

On the other side of the Cathedral is The Cabildo, where the 1803 Louisiana Purchase was signed. The Presbytère was built in 1791 in the style to match the Cabildo. It’s called “Presbytère” because it was built on the site of one, which served as a residence for Capuchin monks. The building served as a courthouse in the late 19th century and is now also part of the Louisiana State Museum, just like The Cabildo.

The Presbytère houses several temporary and permanent exhibits that tell the stories of resilience and exuberance. “The Living with Hurricanes: Katrina and Beyond” exhibit documents the natural disaster, its aftermath, and the ongoing recovery with interactive displays and artifacts.

The magnificent “Mardi Gras: It’s Carnival Time in Louisiana” tells the story of the Carnival traditions in Louisiana, including Cajun Courir de Mardi Gras, Zulu coconut throws, 19th-century Rex ball costumes, and much more. It’s an elaborate collection complemented by interactive exhibits that trace the celebration back to when it started to its present day, including a unique look at how Mardi Gras is celebrated in Louisiana’s rural areas. It’s a must-see museum in the French Quarter, and don’t skip the treasure trove of a gift shop.

Mardi Gras Museum of Costumes & Culture

1010 Conti Street

The Mardi Gras Museum of Costumes & Culture is located between N. Rampart and Burgundy streets in the French Quarter and features the private collection of its owner, Carl Mack, a costumer and entertainer known as The Xylophone Man. It’s one the largest personal collections of Mardi Gras costumes in the city, and it tells the story of the walking clubs, masquerade balls, Mardi Gras Indians, krewe royalty, Social Aid and Pleasure clubs, and Cajun Mardi Gras. The costumes on display include those worn by the Kings and Queens of various krewes, including those worn by Irma Thomas, Al “Carnival Time” Johnson, and the King and Queen of the Tremé Sidewalk Steppers.

The museum’s gallery features four exhibits a year and hosts special events. You can also experience Mardi Gras for yourself by playing dress-up for fun and the selfies in the museum’s vast costume closet.

Mardi Gras Museum at Arnaud’s

813 Bienville Street

This small museum dedicated to the Carnival is located inside the sprawling grande dame of elevated Creole dining, Arnaud’s. The restaurant was founded in 1910 by Arnaud Cazenave, a colorful French salesman who later acquired the honorary title of the Count. The museum opened in 1983 and is named after Germaine Cazenave Wells, Count Arnaud’s daughter, who reportedly reigned as queen of 22 balls between 1937-1968, which is more than any other woman in the history of Carnival.

The collection consists of a couple of dozen of elaborate costumes, both children’s and adult. The oldest costume dates to 1941 and the most recent one is from 1968. The costumes include 13 that belonged to Germaine Cazenave Wells, as well as four of her father’s when he reigned as king, plus her mother’s and daughter’s. The museum’s collection also includes masks, costume jewelry, vintage photographs, party favors, and krewe invitations.

Backstreet Cultural Museum

1531 N. Philip Street

Located in Tremé, which is the area adjacent to the French Quarter right across N. Rampart Street and the oldest African-American neighborhood in the United States, the Backstreet Cultural Museum is as unique as the city itself. It explores the rites and practices of the city’s African-American population that are also interwoven with the French-Creole history of New Orleans. You’ll be led on an unforgettable tour of memorabilia indigenous to Mardi Gras, jazz funerals, second lines, Super Sunday, and other traditions that cannot be found anywhere else in the world.

The museum hosts the largest collection of Mardi Gras Indian costumes in the city. Those are fantastic creations made of beads, feathers and sequins that cost thousands of dollars, weigh hundreds of pounds, and require hundreds of days of painstaking labor, as no element of costume creation is automated. The museum’s collection also includes photos and video footage of Mardi Gras Indians, jazz funerals and second lines.

If you want to see Mardi Gras Indians on the march, the fantastically evocative costumes of the North Side Skull & Bones Gang, and the dazzling performances of the Baby Dolls, head to the Backstreet Cultural Museum early on Mardi Gras Day morning. The North Side Skull & Bones Gang gathers at the Backstreet Cultural Museum and then sets off to wake up the neighborhood on Fat Tuesday, according to the tradition started in the 1800s. You never know when the Mardi Indians show up and where, but the Backstreet Cultural Museum is a reliable spot to catch them.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Must-See French Quarter Museums

Photo courtesy of New Orleans Pharmacy Museum on Facebook

New Orleans tends to be known more for its food, music and nightlife than its museums, but this city actually excels at visitor-friendly educational institutions. Our museums tend to focus on local knowledge subjects that exist close to home: the history of South Louisiana, the roots and variations of the region’s folkways, and similar topics.

A few notable exceptions are the National World War II Museum (located within the Warehouse District, and an easy walk from Canal Street) and the New Orleans Museum of Art (located in City Park, about 15 minutes from the French Quarter by car). Both of these museums are more universal in scope as regards their respective fields of knowledge (World War II and fine art).

In the French Quarter, most museums have a New Orleans, or at least Louisiana-based, focus. Besides being fun and educational, the following museums also constitute a break from the heat — an important factor to consider if you visit during the long summer months.

Note that we’re not including the Museum of Death and the Historic Voodoo Museum in this article. While both of those locales are undoubtedly fun to visit, they’re more tourist attractions than dedicated educational institutions.

Photo courtesy of Louisiana State Museum on Facebook

The Cabildo

Jackson Square

Once the seat of the Spanish colonial government in New Orleans, The Cabildo is now a part of the Louisiana State Museum system. The three floors of this grand structure contain exhibits on state history, ranging from Native American artifacts to profiles of different New Orleans immigrant groups to sober displays on the local slave trade. By dint of its possessions, infrastructure and display content, this is one of the top museums in the city.

The main hall of the building, the Sala Capitular (“Meeting Room”), is a gorgeous space in its own right, offering views out unto the Quarter and the Mississippi River. The room also once served as a courtroom, and was scene of many seminal court cases, including Plessy vs. Ferguson.

Photo courtesy of Louisiana State Museum on Facebook

The Presbytere

Jackson Square

Located almost adjacent to The Cabildo, The Presbytere — so named because it houses clergy members — is also a part of the Louisiana State Museum family. Here, the focus is less on Louisiana history and more on the culture and folkways of the Carnival season, from “krewes” (Mardi Gras parading societies) to the costumes associated with Courir de Mardi Gras in Cajun country. There is also a large permanent exhibition on the impact of Hurricane Katrina, and the city’s post-storm recovery, making a visit here a powerful hybrid experience of celebration, grief and resilience.

1850 House

Jackson Square

Located in the Lower Pontalba Building on Jackson Square, the 1850 house is a glimpse into the well-manicured living conditions of a middle-class 19th-century, free New Orleans family. The city was at the height of its economic power and influence at this time, and the city’s free population enjoyed a standard of living that was unmatched in much of the United States.

Photo courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection on Facebook

The Historic New Orleans Collection

533 Royal Street

The Historic New Orleans Collection (THNOC), a non-profit dedicated to the study of the city, includes a network of historic structures that contain both permanent and temporary exhibitions on regional history. Visitors can explore the Royal Street campus for free or take tours of THNOC’s large collection of preserved properties; the experience speaks to both the historical events of the city and its architectural legacy. Note that THNOC also offers a smartphone app tour, and hosts a long and packed calendar of events and lectures that ought to scratch the itch of even the most obsessed history fanatics.

Photo courtesy of New Orleans Pharmacy Museum on Facebook

New Orleans Pharmacy Museum

514 Chartres Street

Long a favorite of locals, the Pharmacy Museum, located in an 1823-era drug store, is a peek into both the city’s history and the general medical oddities of the 19th century. Inside, visitors learn about questionable medical practices from back in the day — who wants some pills coated in lead paint? Or the insertion of a metal catheter? Argh, that one makes us groan just thinking about it. Don’t get us started on the forceps. The prescription book that old pharmacists once used to keep track of their patients’ medicine is a triumph of ingenuity and engineering in its own right.

The Old U.S. Mint/New Orleans Jazz Museum

400 Esplanade Avenue

A handsome example of Greek Revival architecture in its own right, the Old U.S. Mint produced gold and silver coinage for both the United and Confederate States during its long history as a currency production center. Today it houses the New Orleans Jazz Museum with its exhibitions on jazz music in New Orleans and special events, all under the auspices of the Louisiana State Museum.

Here’s a grim bit of trivia: When the Mint was recaptured by U.S. Marines during the Civil War, a local Confederate sympathizer, William Bruce Mumford, ripped the American flag from the roof of the building and paraded it through the Quarter, where crowds ripped the banner to pieces. For his efforts, Mumford was hung from a flagstaff off the side of the Mint in 1862.

Photo courtesy of Hermann-Grima House on Facebook

Hermann-Grima House and Gallier House

820 St Louis Street

These two historic homes and their attached slave quarters are some of the best-preserved historic structures in the French Quarter. Visitors can learn about the relative opulence enjoyed by the residents of these homes, as well as the conditions of the enslaved workforce that made their lives of comfort possible. A good chunk of the artifacts in both Hermann-Grima House and Gallier House can be traced to the 19th century. Of the many historical homes in the French Quarter, these two buildings are some of our favorites.

New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park

916 N. Peters Street

While it’s not technically a museum (although it does contain some small exhibitions on-site), this branch of the National Park system includes knowledgeable ranger staff who lead tours and lectures that explore the long history of local music and culture. Check the Park’s website for information on live performances.

Backstreet Cultural Museum

1531 St. Philip Street

Located in Treme, just a few blocks out of the Quarter, the Backstreet Cultural Museum must be the most unique museum in the city. Inside, local residents lead visitors through an exploration of the New Orleans “backstreet” — the unique cultural folkways of the city’s African-American population.

Because of its location at the edge of the Caribbean, and a French-Creole history that allowed for the observation of certain traditions, New Orleans’ African-American culture includes a plethora of practices — from second line parades to Mardi Gras Indians — that simply cannot be found anywhere else in the world. With that said, traces of West African heritage can be detected at many levels, from costuming beadwork to the syncopated beat of local parade chants.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Oldest Building Features of the French Quarter

Secluded in the muddle of the French Quarter’s raucous street life linger elements that still impart a kind of stately antiquity. They are Spanish and French-era pieces. Some are rightly celebrated for their survival of the epochs; others, dressed in garish costumes at the shop level, maintain a quiet dignity overhead.

There are only about a dozen known Colonial-era buildings in the Quarter. Surely more would have survived except for two late 18th-century fires. But armed with some simple guidelines, you can recognize the early types.

Check the corner of Chartres and St. Louis streets. There, on the river side of Chartres is a house with a well-known restaurant and a balcony. Note that the balcony is higher than usual, almost too high for the building. The arched, barred transoms under it are bringing light to a short middle floor called an entresol. This is where the old Spanish shopkeeper Juan Paillet kept his wares.

The entresol house was an early experiment in vertical living, with the shop on the ground floor, the warehouse in the middle, and an elegant residence on the upper level. Note the type at 440 Chartres, at Bourbon corner Bienville, at Royal corner St. Louis, and in mid-block at 500 Decatur. Most date to the 1790s.

Brennan’s Restaurant at 417 Royal Street is an example of a more elaborate business and residence of the late Colonial period. Dating to the 1790s, it was once a private bank and home. The Banque de la Louisiane, whose initials are on the balcony, made the building public in 1805. In the early 1900s, it first became a restaurant called the “Patio Royal.” It has been the home of Brennan’s since 1946.

The Girod House at 500 Chartres corner St. Louis, is better known as Napoleon House. Tradition abounds, both as to its one-time purpose as a haven for the deposed Emperor, and in modern times about the charms of its resolutely unregenerate bar. Its rear wing was built just after the Great Fire of 1794. The three-story main part, with its towering belvedere, dates to 1814. Above the tavern is an elegant salon and residence, now restored for entertaining.

Another private home in the grand style was that of Bartolome Bosque at 617 Chartres Street, dating to 1795. Its Arabesque monogram on the balcony represents the style of Spanish Colonial ironworking in New Orleans. This type of home is called a “Creole townhouse.” One accesses the rear by a porte-cochere or carriageway, and ascends the stairs in the rear of the building.

Creole townhouses never had inside stair halls. Bosque’s daughter Suzette was the third wife of the state’s first American governor, W.C.C. Claiborne. On his third try the governor finally married a Catholic, making better friends with the Creoles. She proceeded to outlive him.

Like the Bosque House, the Pedesclaux-Lemonnier House, 640 Royal at St. Peter, has a colonial origin. Begun by the grand old Spanish notary Pedro Pedesclaux, it was sold to a doctor from the islands. In 1811, Dr. Yves Lemonnier had the building enlarged, adding his initials to the balcony. His curved-wall salon on the second floor is the finest in the Quarter. After the Civil War, a later owner added the fourth floor, making it a “skyscraper.” The building was identified with George Washington Cable’s romance “Sieur George” in later decades. Today it is sadly hung with t-shirts.

The old Spanish Cabildo and The Presbytere, or priests’ house, flanking the St. Louis Cathedral, were designed for the Spanish governing council by Guillemard, a French-born architect. The Cabildo, built in the style of Spanish town councils in Spain and the Americas, was begun in 1795.

The Presbytere has never housed clergy, although buildings underlying its site were always the priests’ residence. Also begun in 1795, it was not completed until 1847 and was used for most of its history as a courthouse. The Mansard roofs on both buildings were added in 1847. For nearly a century both buildings have been part of the Louisiana State Museum.

“Madame John’s Legacy,” another Museum property at 632 Dumaine, is also named for a romance by Cable. Dating to 1788, it was built immediately after the great fire that year, duplicating the house type of the French Colonial era. With its free-standing mass and surrounding galleries, it is more like a French West Indies home than a Spanish townhouse.

Still, its first owner was a Spanish officer, and its builder was an American, Robert Jones. The hall-less floorplan here is important. It is three rooms wide and two rooms deep with cabinets and cabinet galleries, a derivative of French-Carribbean house types.

The oldest building in Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley is the stately Convent of the Ursulines at 1100 Chartres Street. Designed by a French-trained military engineer in 1745, it was completed in 1753. It resembles the Continental French buildings of the Louis XV period more than colonial institutions.

The façade we see from Chartres is the rear of the building, which faced the river and was surrounded by herbal gardens. The nuns used their herbs and potager to feed their staff, students, orphans, and soldiers whom they cared for in the neighboring military hospital.

Jackson Square, the old Place d’Armes, is the oldest space in the city. Laid out with the town in 1718, it was always the parade grounds. The city began to make improvements to it in the 1830s, adding trees and walkways. The fence and equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson, hero of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, date to the 1850s.

If you’re planning a stay in New Orleans, be sure to check out our resource for French Quarter Hotels.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Madame Pontalba’s Buildings

Jackson Square, and the land around it, was always for the use of the public, or so it seemed. There was the church (St. Louis Cathedral), the priests’ house (The Presbytere), and the town hall with the prison (The Cabildo). There was the square itself, with its parade ground, and the view of the Mississippi River. The idea of flanking the sides with important buildings was a natural one. The French put the governor’s house there, along with one for the top administrator, the intendant.

Today, the church and the old government buildings are standing in their current incarnations, but flanked on the sides by the stately and privately-built Pontalba Buildings. In 1849, Baroness Pontalba came home from France to her native city to build them on land she inherited.

Somehow, years earlier, the Spanish crown had allowed her father, the notary Almonester, to acquire the lots where the governor’s house had once opened to French-style gardens. In later years, long rows of military barracks succeeded them.

But by 1780, Almonester had two rows of rental properties on them, the base of a fortune in real estate. When the town burned down some years later, he had the wealth to design and reconstruct the church and The Cabildo, especially after he raised rents in the fire-devastated section.

After his death in 1798 his widow, reluctantly, made good on his earlier promise to rebuild The Presbytere also. And so it was that Madame Pontalba’s father before her had shaped the appearance of the public square. In her own time, she would meet the challenge of what was by then a family tradition.

Baroness, a strong-willed designer and a shrewd businesswoman

The Baroness was both a designer and a businesswoman. Would the council relinquish the sidewalk to erect colonnades to render that portion of our city pleasant in all seasons? The design is upon the Palais Royal and the Place des Vosges of Paris! And would the council agree to a tax break for 20 years in light of our expenses in this project, in which we beautify our city?

In an age when houses took six months to complete, the Pontalba buildings were a dozen years in planning and two years in construction. Begun in the spring of 1849, they were not finally finished until the winter of 1851. The Baroness had hired and fired the finest architects of the community, used their plans, then altered the product to her liking.

The result was an amalgam of Creole, Parisian, and Greek Revival tastes and uses. A melange, perhaps, but a reflection of the sophisticated preferences of their creator.

32 stately rowhouses, 16 on each side

The buildings are rowhouses, 32 of them, 16 to the side, each with three stories and an attic. If the outsides with their cast-iron galleries are French and American, the floor plans are Creole.

There are stores downstairs and doors leading to passageways instead of stair halls. At the end of these strange dark passageways, stairs curve gently to the second and third floors and the privacy of residences.

Downstairs, a walkway shelters customers. It is that way because Creoles liked to live upstairs on the second and third floors — the premiere and deuxième étages — and because Madame the Baroness Pontalba wanted it that way.

Elegant Pontalbas spurred the development of Jackson Square

In response to her plans, the council began its own building program. The Cabildo and The Presbytere soon had third-floor, French-style Mansard roofs like those in 19th-century Paris. Churchwardens let a major contract with the architect de Pouilly to rebuild the cathedral.

The council then had the city surveyor design and build the iron fence around the square and redo the inside landscaping. The Andrew Jackson Monument Association gathered funds to erect an equestrian statue of their hero. By the middle 1850s, Jackson Square was in the form it has had for parts of three centuries, substantially unchanged.

Today, the Pontalba buildings are owned by the city and the state, as gifts of its citizens. There are still stores below and residences over them. And tenants carry groceries down the long narrow passageways to the gently curving staircases leading to the upper floors.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Best Live Music Clubs in the French Quarter

Image courtesy of Jeff Shewan

The live music scene in the French Quarter is a feast with many courses, and one that caters to many different appetites.

Looking for Dixieland jazz? Got it. Want to hear Cajun and zydeco rhythms? They come direct from the bayous to Bourbon Street nightly. Maybe you can’t make up your mind between rocking out at a club or cooling down with an intimate acoustic set. Don’t choose — you can easily walk from one venue to another to enjoy a variety of music in one evening.

What follows is a primer on some of the top venues delivering this nightly musical cornucopia.

Buffa’s

1001 Esplanade Ave.

Although it’s technically just past the Quarter in the Marigny, Buffa’s has long been a character-laden outpost of great New Orleans music. The lineup here can range from soulful jazz crooners to piano masters stroking the ivories. It helps that the bartenders pour strong drinks and the food is great. Buffa’s is also open late, till 2 am Sundays through Thursdays and till 4 am on Fridays and Saturdays.

Dragon’s Den

435 Esplanade Ave.

The eclectic variety of music hosted by the two-story Dragon’s Den matches the exotic setting in this singular club. Located at the edge of the Quarter, the intimate space creates a seductive atmosphere with lustrous red hues, Far East décor, a courtyard, and a wrought iron balcony over the tree-lined Esplanade Avenue. Look for all manner of music and a young, very local crowd.

Kerry Irish Pub

331 Decatur St.

It lives up to its Celtic billing with some of the best-poured Guinness stout in town and a welcoming atmosphere. There’s no cover charge for the nightly live music, which includes traditional Irish, alternative country, bluegrass, and rock.

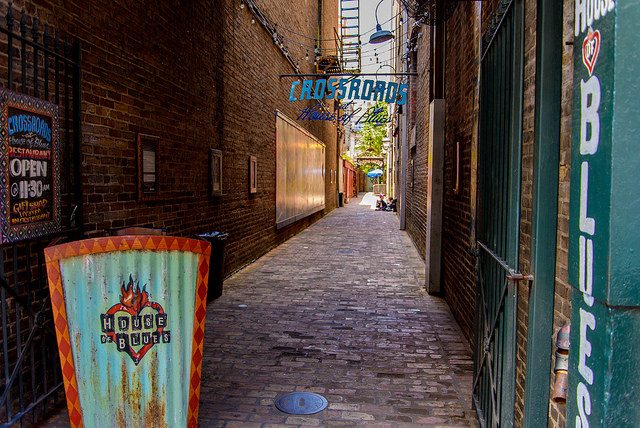

House of Blues

225 Decatur St.

The highly successful House of Blues opened its New Orleans venue over a decade ago, and it has grown into the French Quarter destination to hear nationally touring acts. In addition to the main stage, the club often has music in its restaurant or patio bar, as well as the more intimate concert hall in the adjacent House of Blues Parish, which hosts many local performers.

One Eyed Jacks

1104 Decatur St.

One Eyed Jacks, a popular live music venue formerly located at 615 Toulouse Street, reopened for Mardi Gras 2022 in the space that was formerly occupied by Jimmy Buffet’s Margaritaville and B.B. King’s Blues Club. One Eyed Jacks’ stage is big enough for touring rock bands and even 1950s-style burlesque shows, and the music lineup is as electric and eclectic as ever.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!