Faubourgs Tremé and Marigny Are French Quarter Neighbors Rich in History and Architecture

Top two Faubourg Marigny images by Alexey Sergeev, bottom image courtesy Louisiana Department of Culture Recreation and Tourism.

The historic Faubourgs Marigny and Tremé sit just beyond the French Quarter like old Parisian quartiers. Faubourg, literally “false town,” is the traditional French word for a suburb outside the walls of the city, still governed by the larger metropolis.

Fashionable Esplanade Avenue, once the city commons, is the dividing line between the French Quarter and Marigny and between Marigny and Tremé, while the “Street of the Fortifications” or Rue des Remparts — now Rampart — divides the Vieux Carré from the Faubourg Tremé.

Both New Orleans neighborhoods were born at the turn the 19th century. Bernard Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville inherited his father’s plantation just below the city gates in 1800 at the age of 15. Six years later, he had it subdivided.

Marigny’s development was immediately popular. He spent most of 1806 and 1807 at the office of notary Narcisse Broutin selling 60-foot lots or to prospective homebuilders. On the Rampart side of the French Quarter, Claude Tremé by marriage and inheritance came into possession of an ancient tilery and brickyard dating to the early French colonial period.

The principal residence on it dated to the 1720s. By 1800, Tremé had begun to subdivide and sell the property. In 1810, the city of New Orleans acquired the remainder and resold the lots to residential buyers.

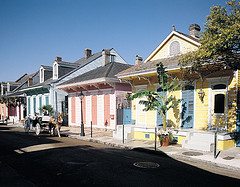

It was in these village-like settings that French-speaking free people of color, working class whites, and immigrants settled in the antebellum period. On crooked extensions of French Quarter streets like Bourbon and Chartres, Dauphine and Royal, they placed their cottages close to the banquettes or sidewalks, the high slate rooftops reflecting the city’s heritage of French-style framing.

Creole cottages and long, narrow “shotgun” houses still dot the streets of the Faubourgs, along with an occasional bungalow. In Marigny, there are also a few large warehouses close to the river.

On the zigzag extension of Bourbon St. as it enters the Marigny from Esplanade Avenue, free man of color and builder Jean Louis Dolliole in 1819 began a cottage for his mother-in-law. He placed it at the angle where the street changed its name to “Bagatelle,” now Pauger.

The pie-shaped lot carved into the point of the pentagon formed by the streets there had a telling effect on his rooftop. Its curious slopes and the rooftop “pan” tiles are well worth a photo — if you can see through the trees on the banquette.

Across the street is another attractive “house in the bend of Bourbon Street.” Built in the 1820s, it features the neighborhood’s first known center hall residence — a narrow, almost timid departure from the prevailing custom of building hall-less cottages.

An open square made a focal and meeting point for each community. Tremé’s fabled Congo Square, where African songs and drumbeats attracted both slave and free populations for Sunday dancing, is now renamed at Rampart and St. Peter St.

Families gathered at Washington Square in Marigny to stroll their babies in carriages, picnic, and listen to parade music. The spires of numerous nearby Catholic churches such as Tremé’s handsome St. Augustine and Sts. Peter and Paul in the Marigny attest to the faith of Creole society, both white and African-American.

They also catered to the immigrant populations of French, Irish and German Catholics who found their way to the Faubourgs where families could afford to rent one side of a double cottage.

By the 1840s, the Faubourgs were bustling with the sights and sounds of working class neighborhoods. The turreted Tremé Market straddled Basin St., extending along the blocks from Marais to North Robertson.

The “grim and brooding” 1833 Parish Prison looked down on the market, its pair of fanciful turreted towers belying their watchful purposes. Basin Street, named for turning basin of the old Spanish Carondelet Canal, was home to factories and lumber mills surrounding the basin where sloops and luggers deposited the pitch and tar and lumber derived from piney Northshore forests.

The old French families of the neighborhood buried their dead in the above-ground tombs of St. Louis #1 and #2 cemeteries, following the burial customs of their ancestors.

Down the middle of the Faubourg Marigny the pioneering steam train that citizens dubbed the “Smokey Mary” departed from its station near the riverfront’s 1840 Port Market. It chugged its way down the neutral ground or median of Elysian Fields Avenue, formed from the right of way of an old sawmill canal that led to Gentilly and Lake Pontchartrain.

The massive plantation house of the Marignys, built in the Spanish period between Elysian Fields and Marigny St., remained in place until the 1830s, its former par terre garden replaced by multi-level commercial buildings. Meanwhile, the old colonial residence belonging to the Tremé brickyard survived until 1926, first as the home of a state-run college and later as the motherhouse of the local Order of Notre Dame of Mount Carmel.

By 1900 the glittering age of jazz and Storyville dominated the Tremé and adjacent French Quarter neighborhood. This gave way in the Great Depression to the construction of a housing project in the heart of the former Storyville.

By the middle twentieth century, “social mobility,” the departure of the old working class families to the suburbs, age and deterioration led to neglect and crime in the old Faubourgs. When the city determined to demolish the historic cottages of nine whole squares of the Tremé, the handful of residents and historians who knew enough to oppose it were powerless.

Change arrived in the 1970s, as citizens began to appreciate what the old Faubourgs meant to New Orleans. Within a couple of decades, both received a spate of new investments, historic zoning, and design review and demolition controls.

While the preservation of neighborhoods is a constant battle, and the Tremé neighborhood continues to struggle with crime and poverty, the bright new colors, jewel-box gardens, and rooftops repaired after Hurricane Katrina promise a brand new century of neighborhood living in the Faubourgs.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who has co-authored the award-winning series, New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf — An Early History.